What’s in a name?

Herald and News

Klamath Falls, Oregon

February 4, 2004

By LEE JUILLERAT

Chatting with Lewis L. McArthur is taking a virtual tour of Oregon history and trivia.

|

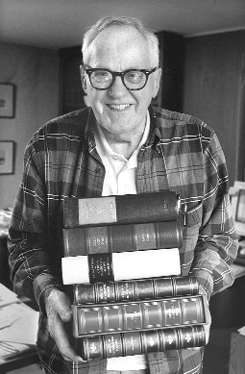

| Lewis L. McArthur shows off a set of the now extremely rare series of editions of “Oregon Geographic Names.” |

He’s been places in Oregon that few others have visited, or knew existed.

He’s learned and researched obscure crumpets of information that, fitted together, create a fascinating picture of the state he loves.

McArthur, 86, is the “dedicated amateur” responsible for keeping alive “Oregon Geographic Names,” a thick compendium of facts, speculations and tales about Oregon places that are, that were, and even a few that might have been. Despite efforts to condense basic information, the new seventh edition published by the Oregon Historical Society Press fills a hefty 1,070 pages.

“People are always calling or writing in,” McArthur explained during a telephone interview of his never-ending quest to ferret information about the state’s place names. “I get letters regularly from people.”

“Geographic Names” was first published in 1936 by McArthur’s father, Lewis A. McArthur. His father, a retired general manager of Pacific Power & Light Co. and director of the Oregon Historical Society, searched through journals of explorers, trappers, traders, naturalists and military men and talked with Oregon pioneers in compiling that first edition.

A second edition followed in 1944 and a third in 1951, shortly before his death. That third edition remained in print until 1961, when Lewis L. created a fourth edition.

“I had an acquaintance with it,” Lewis L. said of taking over the book. “It was his job, and I did what I was told.”

Doing what he was told included driving his then elderly father around the state searching for information. He also watched as his father spent time consuming hours spent proofreading and making corrections.

“I remember my father reading endless galleys,” said McArthur, who embraced the age of computers and the resulting simplified storage of information. “It took some fiddling around, and now it’s a piece of cake.”

He also had the time.

McArthur worked in light steel construction from 1946 to 1986. During those years he was involved with several historical groups, including the American Name Society, Names Branch of the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Mapping Division, and Oregon Geographic Names Board.

“I had the time and the Oregon Historical Society has done the publishing, so I haven’t had to worry about that,” said McArthur, who laughingly terms himself “the current pigeon.”

He’s deliberately maintained the easy writing style developed by his father.

It was also his father who gathered most of the names from Crater Lake National Park, often from discussions with Will Steel, the “father of Crater Lake.”

Steele named many of the park’s geological features, such as Mount Mazama, Wizard Island, Phantom Ship and many other park locations with “supposed Indian names.”

“A good deal on nonsense has been written about the meanings of Indian names,” Lewis L. writes in the book’s introduction. “… They eked out a living amidst hard circumstances and it seems improbable that Oregon Indians ever made up geographic names because of ‘moonlight filtering through water,’ ‘sunshine dancing on the water,’ ‘rose petals floating on water’ or ‘water rippling over pebbles.’ Competent researchers have found that most Indian names were based on much more practical and everyday matters.”

In the Klamath Basin, McArthur often relied on the late Francis Van Landrum and the Shaw Historical Library at Oregon Institute of Technology. Some entries, such as the naming of Malin, came from researching Shaw journals.

The seventh edition of Oregon Geographic Names will probably McArthur’s last. He hopes his daughter, Mary, will handle future editions.

“The interesting thing is the people you meet,” says Lewis L. of four-plus decades of playing the Oregon name game.

He relishes delving through reference materials, including journals, maps, taped interviews and obscure books.

“When you’ve got a real puzzler there’s an strong sense of accomplishment,” McArthur admitted. “You feel really good.”

0 0 0

“Oregon Geographic Names,” the seventh edition, by Lewis A. McArthur and Lewis L. McArthur, is published by the Oregon Historical Society Press. People with corrections and suggestions for a future eighth edition can send information to Lewis L. McArthur, Oregon Historical Society Press, 1200 SW Park Ave., Portland OR, 97205. Information is also available from the Internet at www.osh.org.

Klamath Basin names are part of the fascination for Lewis L. McArthur, the compiler and editor of the seventh edition of “Oregon Geographic Names.”

“I think a lot of the more interesting names were in the Crater Lake area,” believes McArthur. “My father got all those. He got most of them from Will Steel (the ‘father of Crater Lake’), who he knew.”

Among McArthur’s favorites include:

Keno, which had several names “and their history is confusing.” Earlier and-or proposed names included Whittles Ferry, for the ferry operator; Klamath River; and Plevna, from the Russo-Turkish War. The current name honors Capt. D.J. Ferree’s bird dog, Keno, who was named after a then-popular card game.

Braymill, along the Sprague River near Chiloquin, was coined from the last name of William M. Bray, principal owner of the Sprague River Company that operated a sawmill at the location. “Surely,” the McArthurs write, “ingenuity could go no further.” There was also a Bray Mill station about a mile away on the Southern Pacific line.

Malin was named by Czech settlers who came west from Nebraska in 1909. After a Mrs. Frank Zumpfe found a large horseradish root growing nearby, community members agreed to the name Malin for the “famous Bohemian horseradish of Malin, Kutna Hora, Czechoslovakia.

Pokegama, located in the hills above the Klamath River near Keno, was the end of a railroad line to the Pokegama Lumber Company’s mill. Pokegama was actually a change from the name Snow. The lumber company got its name from a place of the same name in Pine County, Minn.

Outside of Klamath County, he relishes the Morrow County community of Hardman. It was originally named Dairyville, although locals called it Rawdog. A nearby community, Adamsville, was coined Yallerdog. After the the Adamsville and Dairyville communities combined, it was called Dogtown by locals before being named for David Hardman, who started a settlement.

– By Lee Juillerat

***previous*** — ***next***