Oregon Congressman Proposes “Aerial Gondola” to Wizard Island

Reflections Visitor Guide

Crater Lake National Park

Summer/Fall 2009

National Park Service

In the summer of 1959, newspapers across Oregon carried headlines about a proposed construction project at Crater Lake National Park. A plan to connect the rim of the lake with the shore of Wizard Island via cable car ignited a heated debate among politicians, the public, and park staff about the appropriate scope of development in America’s national parks. 2009 marks the 50th anniversary of the controversy and seems a fitting time to look back at this interesting, yet largely forgotten, episode in the park’s history.

The congressman making headlines was Charles 0. Porter (1919-2006), a Democrat from Eugene who represented Oregon’s 4th district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1957 to 1961. Upon taking office, Porter made clear his intent to pursue “the installation of some practical mechanical means for transporting people from the rim down to the lake so that more persons could enjoy boating, especially the many old people who visit the lake.”

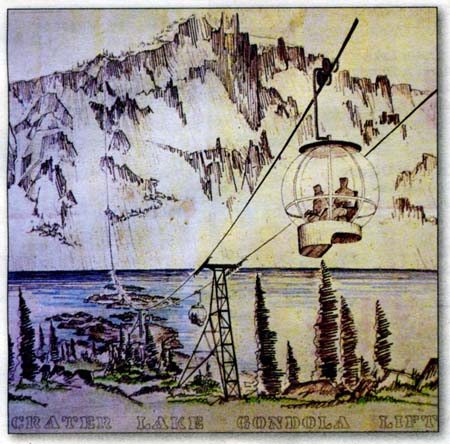

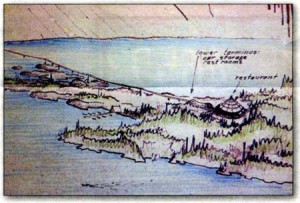

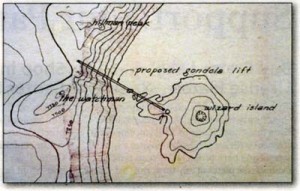

Several months later, while on a trip to Disneyland, Porter hit upon the idea of an aerial gondola. One of Disney’s newest attractions at the time was a ride called the Skyway. In less than two years of operation, it had transported over 6,300,000 guests through the air from Fantasyland to Tomorrowland. Impressed by the Skyway, Porter contacted the ride’s Swiss manufacturer to determine the cost and feasibility of installing a similar conveyance at Crater Lake. He hired a firm of Eugene architects to produce preliminary drawings, and he mailed a questionnaire to 100,000 members of his congressional district to garner support.

Public reaction was mixed. In editorials, the state’s newspapers alternately praised and condemned the idea. Salem’s Oregon Statesman proclaimed its approval: “Every year thousands of people, because of their age or physical ailments, stand at the rim wishing they could make the trip to the lake’s edge. . . Our national parks should be a place for their enjoyment as well as the rest of the population.” The Medford Mail Tribune, however, called the plan “abominable. . . . Crater Lake was created as a great National Park because it is one of the world’s gems of scenery.. . .To slap a mechanical contrivance on the slopes of that unsurpassed caldera. . . smacks of sacrilege in our book.” And Charles Porter’s congressional colleague, Representative A1 Ullman, whose eastern Oregon district actually encompassed the park, was unswayed: “We don’t want a Coney Island atmosphere in our national parks.”

National Park Service managers were also firmly opposed. It’s correct, as Porter argued, that neither the 1902 act of Congress that created Crater Lake National Park nor the 1916 act that created the National Park Service expressly prohibits aerial lifts and tramways. The legislation does, however, require that national parks be managed in such a way that their features and scenery be left “unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”In the words of then superintendent Thomas J. Williams, since Crater Lake is this park’s primary scenic feature, “A tramway, chairlift, or other similar device would violate that mandate and irreparably mar the scene we are charged to protect.”

In the face of such determined opposition, plans for the gondola lift stalled. And when Charles Porter lost his House seat in the election of 1960 to Republican Edwin Durno, public interest faded. There would be no Skyway to Wizard Island.To be sure, the appropriateness of any park construct be it road, visitor center, or hiking trail-is, in the end, a judgment call. Park managers must strike a careful balance between conserving park resources and providing for visitor enjoyment. When in doubt, however, protection of park features is paramount. Naturalist Carl P. Russell once put it this way: “It seems to me that we should have regard for the many generations of park visitors to come. They can tolerate our failure to ‘develop’ Crater Lake but they will not forgive us for mutilation.”

In the face of such determined opposition, plans for the gondola lift stalled. And when Charles Porter lost his House seat in the election of 1960 to Republican Edwin Durno, public interest faded. There would be no Skyway to Wizard Island.To be sure, the appropriateness of any park construct be it road, visitor center, or hiking trail-is, in the end, a judgment call. Park managers must strike a careful balance between conserving park resources and providing for visitor enjoyment. When in doubt, however, protection of park features is paramount. Naturalist Carl P. Russell once put it this way: “It seems to me that we should have regard for the many generations of park visitors to come. They can tolerate our failure to ‘develop’ Crater Lake but they will not forgive us for mutilation.”

Even so, the motivation behind Porter’s plan was laudable. The Cleetwood Cove Trail, which today provides the only legal access to the shore of Crater Lake, is a steep and strenuous trail not suited for anyone with mobility impairments or in subpar physical condition. While most people would agree that the most spectacular views of Crater Lake are to be had from the rim, a boat tour on the lake reveals features of the caldera that can’t be seen or experienced from above.

In fact, from the park’s earliest days, a number of visionaries, among them park employees, have dreamed of providing increased access to the lake shore. Will Steel, the park’s second superintendent and perhaps its greatest champion, called for the construction of a 4-mile (6.4-km) road, descending counterclockwise inside the caldera from Crater Lake Lodge to the shore near the Phantom Ship. “With such a road in operation,” Steel enthused, “instead of one per cent of visitors going to the water there will be 100 per cent.”

In the 1940s, park superintendent Ernest P. Leavitt argued in favor of drilling an “inclined tunnel” from the West Rim Drive to the water below Watchman Peak. Motorists would have emerged from the tunnel to find a protected yacht harbor, rental rowboats, and a facility for purchasing fishing tackle, sandwiches, candy, and magazines. Other entrepreneurs of the era petitioned the National Park Service to allow them to access the water via elevator, chair lift, and funicular railway.

In each of these cases, the eventual decision was the same: that these measures, no matter how well-intentioned, would represent an excessive disturbance of the park’s natural state and an unacceptable impairment of its scenery.

Nevertheless, so strong is the human urge to descend below of the rim of the Crater Lake caldera that, in all probability, it’s only a matter of time before someone else calls for an escalator, a trolley, or a giant crane, and the whole debate begins anew.