Crater Lake Wildflowers and Their Rapid Growth

At elevations from 6000 to 8000 feet, like those near the Rim of Crater Lake, winter weather exists during a major portion of the year. Records kept in the Chief Ranger’s office show snow on the ground from October until June with snow often recorded in September and sometimes remaining until July. Compared with the season of 1951 – 52, when snowfall was almost a record, the total reaching 835 inches, (Hallock, 1952) only 571 inches were recorded for the year of 1952 – 53. Of this amount, 6.8 inches fell in June and approximately 108 inches remained on the ground at the Rim Campground July 1st. Hence the late season. The Rim road around the Lake was not completely opened until July 30th and the trail to the Lake, August 1st.

On the bank bordering the Sinnott Memorial walk, snow disappeared July 10th. Twenty days later, prickly currant, Ribes lacustre Poir, had put on new leaves and a profusion of greenish pendulous flowers.

The smooth wood rush, Luzula glabrata Hoppe, cannot wait for the snow to melt but sends up bright green, grass-like leaves through the thinning snow, often while it is three inches deep. This plant is a perennial, the stoloniferous stems staying alive underground during the long winter months.

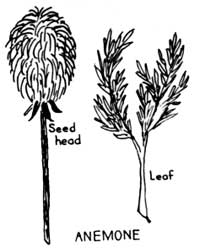

The western windflower, Anemone occidentalis Watson, is not-able for it’s quick appearance when the snow melts. In less than a week the finely divided leaves appear, and two weeks later the flower stem is crowned with a white flower, the center filled with canary yellow stamens. This in turn is short lived, and the attractive greyish seed head, resembling a wind blown cloud, takes its place. Like so many members of the buttercup family, the flower has no petals – – the showy sepals taking their place.

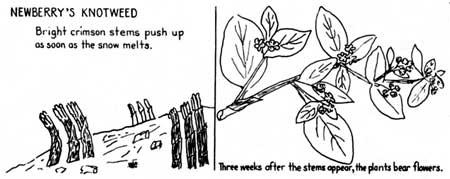

For speed in completing its annual cycle, one must mention one of the commonest of Crater Lake flowers, Newberry’s knotweed, Polygonum Newberryi Small. The history of several recorded plants on the Garfield Peak trail was as follows: Two days after the snow melted back, bright red stems pushed through the drying soil. A week later green leaves were in appearance, and the plant was about three inches tall. Seven days later, short spikes of greenish flowers were showing, and the plant had attained the apex of its flowering season just 24 days after the bright red stems pushed through the earth. Very quickly the green chlorophyll in the leaf disappears, and the hillsides are brightened by the red and orange tints of this fast growing little knotweed. This is just another of the many plants which take advantage of the brief hours of summer sunshine to complete their short yearly cycle before autumn frost and snow terminates activity for another year.

Reference

Hallock, Louis W. 1952. The big snow of 1951-52. Crater Lake Nature Notes 18:3-5.

Observations and Census of the Black Bear in Crater Lake National Park

Crater Lake Bears. From kodachrome by Welles and Welles.

Crater Lake Bears. From kodachrome by Welles and Welles.

The Olympic black bear, Euarctos americanus altifrontalis (Elliot) was first noted at Crater Lake from the standpoint of numbers in 1896 when a biological survey was made of the mammals in this area. At that time the black bear was reported to be uncommon (Merriam, 1897). According to one ranger naturalist, bears were so scarce at one time that it was feared they would become extinct in this area. It seems, however, that in 1919 hopes for their survival took a turn for the better when a long, starved-looking female bear put in her appearance (Wynd, 1930).

She soon gave birth to a pair of twins and, after rearing them to the independent stage, wandered off one day to a nearby logging camp. Having learned to place her confidence in human beings, she sat down by a tent and waited to be fed–but instead of food she received a lead slug. The twins, named Jemima and Buster, carried on successfully and are said to be the forerunners of most of the bears now found in the park.

The total number of bears observed in the fall of 1933 was fourteen. This census was taken after the first heavy snowfall, at which time the bears relied on food scraps obtained at the dining hall near park headquarters (Canfield, 1933). According to Wallis (1947), Wildlife Ranger Wilfred Frost observed forty-two bears on August 31, 1939. Thirty-three were black, the remainder being of the brown color phase. Wallis himself estimated the bear population in 1947 to be between twenty and thirty in number. From the foregoing records it is evident that the census of bears during the past 50 years is rather incomplete and lacks data in regard to methods used, percentage of various color phases and any breakdown into age groups.

Cinnamon Cub. From kodachrome by the author. Cinnamon Cub. From kodachrome by the author. |

“Where can I find a bear?” “How many bears are there in the park?” Questions such as these stimulated me to pursue an active program of observations on the bears in the park. During the summer months of 1953 daily records were made in regard to size, color, number and habits.

Although the National Park Service long ago discontinued bear feeding “shows” and prohibits the feeding, teasing and molesting of bears, with the welfare of both bears and visitors in mind, the animals are occasionally seen crossing the roads in various places in the park. They frequently wander through the campgrounds looking for food that may not have been packed away in a secure place. The bear is not a rare mammal in Crater Lake National Park.

The following table is a record of the quantitative results obtained. To obtain this data a segregation plan was used. First, the several females and their first year cubs were segregated, the second year cubs were then differentiated from medium and full size single adults. Daily observations included many repeats which were hard to distinguish at first but soon various differentiative characteristics such as general size, obesity and sex became helpful in individuals within a given category.

It should be understood that by no means do I consider this to be complete because such a field census undoubtedly includes some duplication, and some bears would go unobserved in an area covering two hundred and fifty square miles. However, this is an attempt to start filling in a gap that can be added to from time to time as better methods and additional observations are employed.

| ADULTS | ||

| No. | Size | Color |

| 8 | Full grown | Black |

| 6 | Full grown | Brown |

| 4 | Medium size | Black |

| 4 | Medium size | Brown |

| 22 | ||

| CUBS | ||

| No. | Size | Color |

| 5 | First year | Black |

| 7 | First year | Brown |

| 1 | First year | Cinnamon |

| 3 | Second year | Black |

| 3 | Second year | Brown |

| 19 | ||

Total 41

The only record of a bear observed nursing her young in the park prior to this year was made in 1939 by Mr. Frost (Wallis, 1947). He observed a mother bear nursing triplets near one of the disposal areas. Ranger Naturalist John Mees observed a mother nursing her twins in June, 1953 According to Mees, the mother bear assumed a prostrate position by lying on her back; then with the help of her front paws the two young were arranged in orderly fashion on her ventral side for nursing. Mr. Mees observed them from a distance of fifty yards and noted that loud gurgles could be heard that far away.

As can be seen in the table, which notes the number of bears observed, there was apparently only one cinnamon cub for the 1953 season. This little cinnamon bear had a black twin which was considerably larger. One day the mother crossed the road and, since the snow banks were rather steep on either side, the cubs had to really scramble to climb over them. In fact, the poor little cinnamon could hardly make it up. He rested about half way up one bank and then made it on the second attempt. Since he was not seen again during the season, I wondered if some male bear had killed him.

Two of the full grown male bears, one black and one brown were very conspicuous because of their unusually large and seemingly long front legs. Several of the park staff noted this unusual anatomical feature. The older males also have very large, hard-looking heads which one cannot mistake in trying to segregate the groups.

References

Canfield, David H. 1933. A Bear Story. Nature Notes from Crater Lake National Park6(1):8-9.

Merriam, C. Hart 1897. The Mammals of Mount Mazama. Mazama 1(2): 204- 230.

Wallis, Orthello L. 1947. A Study of the Mammals of Crater Lake National Park. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Oregon State College, Corvallis. 91 pp.

Wynd, F. Lyle 1930. Triplets. Nature Notes from Crater Lake 3(1):2-6.