So Many Tiny Birds

The hillsides above Castle Crest Wildflower Gardens were covered with many kinds of colorful flowers. One could hear the buzzing of the busy bees. But such large bees. No, they couldn’t be, they were tiny birds – dozens of little zooming hummingbirds, flashing by like jet airplanes and oh, so busy. Thus, I became acquainted with one of the tiniest birds in the park and in the United States.

They proved to be the rufous hummingbird, Selasphorus rufus (Gmelin), which is by far the most abundant hummingbird in the park, as in all of Oregon. The dazzling copper-red gorgest flashing in the sun and the rufous or reddish-brown back proved to be his marks of distinction. The females and young are much more difficult to recognize.

In addition to the beautiful iridescent coloring, I was fascinated with their continuous activity. They must be very nervous, as they are always on the move, seldom stopping to rest. The average camera is quite unequal to their size and speed. When they are not darting from one flower to the next, they are chasing each other in great frenzy.

This year I noticed that the rufous was first apparent in large numbers about the middle of July, feeding in the blossoms of big huckleberry, Vaccinium membranaceum, Dougl., a little above Castle Crest Gardens. By the first of August, the young were all flying, and the scarlet gilia, Gilia aggregate, (Pursh) Spreng., red monkeyflower, Mimulus lewisii Pursh and columbine, Aquilegia formosa Fisch., helped provide for the increased numbers. They seem to prefer tubular flowers, such as those on members of the figwort family, which their long bill is capable of penetrating. This year the Castle Crest wild flowers were very abundant, which no doubt accounts for the appearance of so many hummers.

I happened to have occasion to be on all of the main trails during the first week in August. I noticed female and juvenile rufous hummingbirds along each of them, although I seldom saw the males.

During the launch trip around the lake on the morning of August 8, a female rufous power-dived my wife, who was wearing a bright red sweater. It hovered only about two feet above her head before it flew off toward the Phantom Ship, which was nearby.

The calliope hummingbird, Stellula calliope (Gould), is also found in the park, but these birds are relatively scarce here and are found mostly at the lower elevations. The calliope is the smallest bird in the United States, not much larger than a large bumble bee. It is also very colorful, the gorgest having a rayed or stripes rose-purple effect, in contrast to the solid flame-red of the rufous.

Beautiful flowers and fascinating birds are a grand combination. I personally invite you to take any one of our trails, around the first of August, for this impressive treat.

References

Farner, Donald S. 1952. The Birds of Crater Lake National Park, University of Kansas Press. xi, 187 pp.

Gabrielson, Ira N. and Stanley G. Jewett. 1940. Birds of Oregon, Oregon State College Press, Corvallis. xxx, 650 pp.

Porcupine Encounters

The yellow-haired porcupine, Erethizon dorsatum epixanthum Brandt, is frequently seen waddling slowly beside our park highways, especially at night. When in a hurry, however, this fellow can ramble along at about two to three miles an hour. This speed was estimated by clocking a porcupine from an automobile while I was traveling the Rim Drive near Dutton Ridge. The porcupine was held on the highway by the stone retaining wall, thus providing a good opportunity to time him while he was moving in a fairly straight line.

It is often said that a porcupine is an animated bundle of quills. He is armed with twenty to thirty thousand of these barbed needles which form his main, and almost only, means of defense. This equipment is adequate for protection against the great majority of enemies. An interesting correlation with low birth rate can be found here, for porcupines are almost always born singly. A rare occurrence of twins is suggested by the observation of an adult with two youngsters in the Castle Crest area during July, 1947, by Ranger-Naturalist Gordon P. Walker (Walks, 1947).

A vigorous slap by the porcupine with his powerful tail can send quills well into the nose and face of any animal inexperienced in dealing with these creatures. I have observed several small porcupines along Dutton Ridge and they have invariably kept their tail between themselves ant me when they were cornered.

A few natural enemies of the porcupine become expert at killing them without picking up a collection of quills. The porcupine is usually forced into a corner and snatched by the nose. With a quick flip it is turned onto its back and then attacked at the soft, unprotected underparts.

Yellow-haried Porcupine From Kodachrome by Richard M. Brown |

Early in the summer of 1952, two hollow porcupine “shells,” consisting of nothing but fur and quills, were found near Castle Crest. Proof as to the identity of the animals that had killed them could not be found, but bear tracks were seen in the snow around the carcasses. Since numerous bears were seen in the same area at various times, it seems quite possible that these animals were responsible for the fatal encounter. A similar skin was found in the Castle Crest Wild Flower Garden in the early spring of 1946 (Wallis, 1947).

During the month of July, 1953, I was so surprised by a porcupine along the banks of Sand Creek that I nearly lost my footing, which would have meant a sudden dip in the creek. Luckily only the porcupine slid down the loose talus slope into the stream. This porcupine apparently disliked swimming and refused to swim across the stream. Instead, he floated along with the current until he was able to climb back onto the same bank. Wallis (1947) reports having met a porcupine while walking on the stream bank in the steep canyon of Patton Creek. This particular animal, upon being disturbed, plunged into the water and seemed to cross to the other side with no trouble at all.

Episodes such as these with porcupines make the study of our local inhabitants an absorbing experience. With a little patience, you also will surely have interesting encounters during your stay in the Park. And perhaps you will learn some new and unusual feature of the wildlife in the park.

References

Cahalane, Victor H. 1947. Mammals of North America. MacMillan Co., New York. x, 682 pp.

Sumner, Lowell and Joseph S. Dixon. 1953. Birds and Mammals of the Sierra Nevada.University of California Press, Berkeley. xvii, 484 pp.

Wallis, Orthello L. 1947. A Study of the Mammals of Crater Lake National Park.Unpublished Master’s thesis, Oregon State College, Corvallis. 91 pp.

Two New Bird Records

On the morning of August 22, 1954, while leading a field trip along the lower part of the Garfield Peak Trail, I first heard and then saw an adult male goldfinch, Spinus tristis(Linnaeus). The bird was in bright yellow plumage and was at a distance of between fifty and one hundred feet as it fed on the ground and made several short flights.

The other, more spectacular, observation was made on the afternoon of September 3, 1954. While on duty at Sinnott Memorial, I observed a bird of unusual appearance circling over the lake shore directly in front of and below that observation point. It continued to soar, with some flapping of its wings, above the shore of the lake between Sinnott Memorial and the foot of the lake trail until it was high overhead. It then glided off in a southward direction.

I believe the bird to have been a jaeger, a pelagic bird seen infrequently along the coast and only rarely inland. It was quite dark above, white below, and had a noticeable black cap. The most striking features of the bird were its elongated central tail feathers and its long, tapering, pointed wings. The shape of the tail feathers indicate that the bird was either a parasitic jaeger, Stercorarius parasiticus (Linnaeus), or a long-tailed jaeger, S. Iongicaudus (Vieillot); its trim appearance and graceful flight would seem to indicate the latter bird.

The jaeger was observed with eight-power binoculars in good light for about five minutes.

Reference

Farner, Donald S. 1952. The Birds of Crater Lake National Park. Lawrence, University of Kansas Press. xi, 187 pp.

Breeding Activities of Crater Lake Birds

During the summer of 1954, several nesting records of interest were added to the park’s ever-increasing store of ornithological information. Nests were found, each for the second time only within Crater Lake National Park, for two species. These were the ruby-crowned kinglet, Regulus calendula (Linnaeus), and the Pacific nighthawk,Chordeiles minor (Forster).

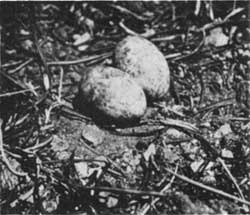

Nest & Eggs of Pacific Nighthawk From Kodachrome by Richard M. Brown |

On July 16, between lower Munson Meadow and the road to Annie Spring, at an elevation of about 6,200 feet, I discovered the ruby-crowned kinglet carrying food to a nest crowded with five nearly-grown young. The nest was situated in a lodgepole pine, near the outer end of a dense mass of branches about ten feet above the ground. It was so well hidden as to be only barely visible from below. The bulk of the nest was made up of dead lichens, with much deer hair woven through it. A few bits of rabbit fur and red string were scattered around the top and sides. Feathers lined the interior, one of them apparently coming from a mountain bluebird. The nest measured four inches in greatest diameter and three and one-half inches in depth; the cup was only one and three-quarters inches wide and one and one-half inches deep. The empty nest was collected later in the summer and is now in the park collection (CLNP 632).

The other “find of the year” was the discovery by Mrs. Stine, wife of Ranger J. Francis Stine, of a nesting nighthawk about one-third mile southeast of the Lost Creek Ranger Station (Stine and Stine, 1954). The two eggs were found on the ground in a tiny clearing from which the pine needles and pebbles had been pushed aside. The site was a few feet from a small group of lodgepole pines, typical of that relatively open woodland. Discovered on July 18, the eggs hatched a day apart, on the 27th and 28th. By mid-August, the two downy young could still be found by a careful search of the area within several hundred feet of the nest.

On July 19, a pair of violet-green swallows, Tachycineta thalassina (Swainson), were seen entering the same cavity in one of the Wheeler Creek pinnacles that was evidently used in 1953 as a nesting site. Mountain chickadees, Parus gambeli Ridgway, nested in a cavity at the top of a four-foot mountain hemlock stub in the South Entrance utility area. On June 30, several young and one of the adult birds were found in the hole. The parent made no effort to escape but showed its agitation by hissing and pecking at the wall of the cavity. A red-breasted nuthatch, Sitta canadensis Linnaeus, was seen on June 23 carrying fragments a wood out of a hole twenty feet up in a dead mountain hemlock near Duwee Falls.

Western tanagers, Piranga ludoviciana (Wilson), were again abundant in the vicinity of Park Headquarters and were especially numerous around the Lost Creek Ranger Station — until early August, when they became much less noticeable. An earnest attempt was made to locate a nest, since one has never been found in the park, but observation of females and singing males produced no results in this respect. While searching in the vicinity of lower Munson Meadow on July 12, one male was observed pursuing another, suggesting territorial behavior. On the 14th, a half-mile outside the south boundary, a pair of western tanagers were seen going to what appeared to be a nest in a dense tuft of needles at the outer end of a ponderosa pine branch about twenty- five feet above the ground. On subsequent visits, however, neither bird was seen. Three of four nearly-grown young tanagers were observed while being fed by a female near Castle Crest Wildflower Garden on August 7.

Other records of juvenile birds being fed by parents during this summer are: a gray jay,Perisoreus canadensis (Linnaeus), at Cold Spring Campground on June 23; several ruby-crowned kinglets in the lodgepole pine forest a mile northwest of Lost Creek Ranger Station on July 19; three hairy woodpeckers, Dendrocopos villosus (Linnaeus), near lower Munson Meadow on July 23; a Steller jay, Cyanocitta stelleri (Gmelin), at Annie Spring Campground on July 28; and an olive-sided flycatcher, Nuttallornis borealis(Swainson), being fed a large dragonfly along the Lake Trail on August 11. With the exception of the last, all of the birds were actively following the adult.

References

Farner, Donald S. 1952. The Birds of Crater Lake National Park. Lawrence, University of Kansas Press. ix, 187 pp.

Stine, J. Francis, and Mrs. Marcella Stine. 1954. Lost Creek Ramblings. Nature Notes from Crater Lake 20, pp. 18-20.

Wood, Robert C. 1953. Nesting birds. Nature Notes from Crater Lake 19:31.