Visited in Midwinter: A Trip to Crater Lake in 1897

Editor’s note: The following article represents the first recorded account of a winter visit to Crater Lake. It appeared in a Klamath Falls newspaper 100 years ago.

We left Fort Klamath on Tuesday, February 23, at 2:30 p.m. mounted on showshoes and drawing a hand-sled on which we packed our provisions and blankets and went that afternoon as far as Chas. Martin’s place at the upper end of the valley.2 That night the mercury went down to four above zero which made snowshoeing fine the next day, until we got within four miles of Bridge Creek, where the thermometer stood 45 degrees in the shade and 83 degrees in the sun, which temperature softened the snow to such an extent that it made shoeing impossible.3 We then ate our noonday lunch, put our shoes on the sled and footed it through the soft snow above our knees to Bridge Creek, where we arrived at 6 o’clock that evening, all tired out, having made only four miles that afternoon. After eating supper we made our bed down, or rather up, on fourteen feet of snow. Of course this was only a drift, as we did not have time that evening to look around for a shallower snow-bank upon which to make our bed.

Next morning we arose at daybreak, made breakfast and took the depth of the snow on the ledge across the creek, which we found to be only 8 and one-half feet deep. The thermometer registered that morning 28 above.4

Skiers going to Crater Lake from Fort Klamath in 1918. Photo by Alex Sparrow. |

Again we mounted our shoes and shoved our way slowly up Annie Creek Canyon, arriving at Cold Camp at 11:30 a.m., where we lunched and rested.5 We found the snow to be only 8 feet deep there. We had to abandon our shoes going up the summit and “take it afoot,” as the mountain was so steep that our shoes would slip back. However, we arrived on top at 1:20 p.m., and found the snow there to be 10 feet deep.6

When we got on the summit, instead of keeping [to] the road leading down on the other (north) side, we turned to the right and went along the backbone of the mountain which we thought would be a gradual slope all the way up to the lake and would avoid footing it down the mountain and crossing the swale and up the steep mountain again on the other side to the lake.7 But two miles of extremely difficult traveling along the steep backbone, through snow up to our waists, brought us to the conclusion that we had better abandon our roundabout trip and make our way down the mountain side to the camping place at the foot of Crater Lake Mountain, which we did, arriving in camp at 5:25 p.m. It would be useless to say that we were wet through to the waist and all tired out. However, we lost no time in getting a few slabs of thick fir bark upon which to build our fire by which we dried our clothing and cooked our supper.

Next morning, being the 26th, we left camp at 6 o’clock without breakfast, for the lake. Two miles up the steep mountain brought us to the brink of the most picturesque view which we were privileged to behold. There was the lake away down in the almost bottomless pit wrapped in the snowy gause of silence, while the gentle rays of the rising sun kissed the snowcapped peaks of the surrounding mountains as the gentle breeze rippled the inky water far below. There was a soft breeze blowing from the south, while the mercury stood at 38 in the shade and 76 in the sun.

There was a thick skim of ice on the west end of the lake extending eastward from the bank some two hundred yards and probably half a mile long north and south.

The snow under the trees on Mrs. Victor’s rock was five feet deep, while back farther in the open it was 10 feet, and seemed to be of an even depth all around the south side.8It was impossible to go down to the water as the snow which had blown from the south, broke off abruptly from the top for probably one hundred feet below when it would take its regular slant until within about the same distance from the water where it would again form another perpendicular bank. The water seemed to be as black as ink. We had a very strong glass with us, but we could not see any beach at the water’s edge.

Photo by Rudy Lueck, 1935. |

The snow was all off the trees on Wizard Island and surrounding bank, while the strip of land running out northwest from the island seemed to be a floating snowdrift.

We spent about an hour and a half at the lake when we turned our shoes homeward, where we arrived on the evening of the 27th.

No pen can describe the picturesque views we beheld on our trip. No orator could do justice to the mountain breeze, the crisp mild air and delightfully cool water bursting gleefully from the sides of the mountains. Now we are passing along one of nature’s wonderful creations — a canyon — where massive perpendicular rocks rise hundreds of feet on either hand. Again in open space, with massive peaks all about us, do we find ourselves. These nearest spurs are snow-capped and uninviting; those at a distance jagged and rugged.

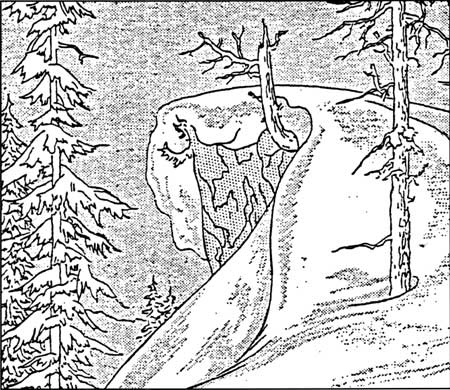

The scenery at times partakes of weird and grotesque appearance, and is then grand and awful. Odd forms of snow, sometimes resembling mammoth animals, overhang our path or project from the mountain beyond and appear ready to leap upon us. Over all this magnificence, enhancing the picture to a marvelous degree, shone the azure vault above.

It is true we found places that were extremely difficult of traveling over, and yet how foolish we would have been to remain at home because of them. Deep gulches must be crossed, narrow and sliding ones were not infrequent. More than once did we hold our breath as we passed over some of these places, but a steady nerve and lots of energy were all that was necessary to carry us through.

Notes

1 Originally titled Visited in Midwinter: A Trip to Crater Lake Through Unfrozen Snow — A Difficult But Interesting Adventure. It was originally written as a letter to Captain O.C. Applegate and subsequently published as a newspaper article in March 1897.

2 The author was in the company of his brother, P. S. Loosley. Martin’s homestead was about 1.5 miles north of the town of Fort Klamath near what is presently Highway 62. The brothers would have gone approximately five miles that afternoon since the Loosley Ranch is located south of town.

3 This area is where the ponderosa pine and white fir forest gives way to lodgepole pine, a transition readily seen along the south entrance road. Bridge Creek is now called Pole Bridge Creek.

4 Much of the temperature difference between the two days was due to the downslope movement of air. This often makes the area around Fort Klamath (at 4200 feet in elevation) much colder than a site on Mount Mazama such as Pole Bridge Creek, some 1600 feet higher.

5 The vicinity of Annie Spring.

6 Their route corresponds to the trail which connects Annie Spring with the Pacific Crest Trail.

7 They tried traversing Munson Ridge instead of using the wagon route which roughly corresponds to what is now the Dutton Creek Trail.

8 Victor Rock is where the Sinnott Memorial is presently situated. The south side described by Loosley was named Rim Village in 1924.

Winter Illustration by L. Howard Crawford, Nature Notes from Crater Lake, 8:1, July 1935.

On an Old Road to Crater Lake

Oregon is a state where historic trails are of more than passing interest. Since one or more of them were crossed by the forebears of many current residents, these trails are more than a conceptual link with the past. Reenactments and other commemorative activities along the Oregon and Applegate trails, for example, have given associated wagon ruts, blazes, inscriptions, and campsites special status as symbols of hardy immigrants struggling to reach a promised land.

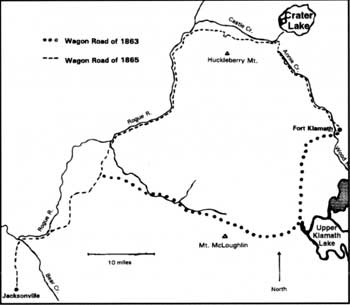

There are, of course, other types of 19th century trails in Oregon, ones that have little to do with a long treks toward a future home. Many of these carried stock or supplies, but were also used on outings by people seeking recreation and inspiration. One of them crossed Oregon’s only national park and has largely escaped widespread notice. It was constructed in 1865, after the U.S. Army recognized a need for better access between its post at Fort Klamath and supply points such as Jacksonville in the Rogue River Valley.

Map by Steve Mark. |

Although a track around Mount McLoughlin had been built at the time of the fort’s establishment in 1863, that road proved to be steep and difficult.1 Consequently, a company of soldiers commanded by Captain F.B. Sprague found a route in the summer of 1865 which made crossing the mountains considerably easier. Much as Highway 62 presently does, the route stayed above and west of Annie Creek Canyon and found a relatively easy crossing of the Cascade Divide at an elevation of 6,300 feet. From there they began a descent, avoiding Castle Creek Canyon by staying south of it, and in 20 miles or so reached the Rogue River near what is now the settlement of Union Creek.

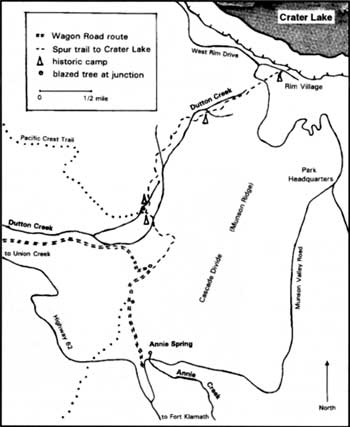

The soldiers saw Crater Lake and several of them wrote about its wonders in newspaper accounts, but the new road came no closer than two miles from the rim. It was left to a tourist party formed in Jacksonville during the summer of 1869 to blaze a track from the Army’s wagon road to the area now known as Rim Village.2 They went up Dutton Creek rather than Munson Valley (where the road connecting Rim Village with Highway 62 currently runs) until 1905 because the upper end of the latter was difficult to traverse without improvement by heavy equipment.

19th century visitors sometimes left carvings on trees near their camp. Photo by Steve Mark. |

Establishment of Crater Lake National Park in 1902 eventually paved the way for a series of road improvements. Part of the wagon road was overlaid with asphalt or chopped into segments by realignments and eventual widening of Highway 62. Despite the changes, portions of it remain. The wagon road can be seen in places as a narrow depression, while in others naturally seeded trees have filled the compacted bed. Blazes are still apparent on living trees or snags and are sometimes used to find the old alignment where ruts or depressions are absent.

Approximately four miles of the first road to lead visitors to Crater Lake are fairly evident on a hike which begins at Annie Spring. A tell-tale depression quickly becomes evident on the downhill side of a more recently constructed hiking trail which climbs toward the divide. Some ruts can be seen from the hiking trail just above the water tank. Close inspection of the adjacent trees reveals that blazes have healed after more than a century, but so- called “cat faces” can be seen at eye level. Hatchets long ago left hack marks on several trees at the divide, where the hiking trail followed from Annie Spring merges with the Pacific Crest Trail. From this point it is another mile or so to the next trail junction where the Dutton Creek Trail begins.

The intervening distance will reward a sharp-eyed hiker looking for evidence of the wagon road. Upon descending roughly one half mile from the divide, a large snag to the left can be seen. A triangular cat face on it indicates where the wagon road diverges from the trail to Crater Lake that was first blazed in 1869.3 A few hundred yards further on, the hiking trail crosses several streams which feed upper Castle Creek. This area once served as an informal camp, and there are at least two places where blazes are accompanied by tree carvings with names of early visitors. More important for botanists and others interested in saving rare plants, this is where a member of the phlox family with small purple flowers was discovered in 1896. The camp area has thus become the type locality for Collomia mazama, and populations there continue to be an important reference point for scientists studying the plant’s life history and reproductive biology.

Map by Steve Mark. |

Much of the modern Dutton Creek Trail closely corresponds with the track first blazed in 1869. Blazes on Mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana) and Shasta red fir(Abies magnifica-procera) indicate where several subsequent realignments of the trail occasionally diverge from the original route.4 Roughly three-quarters of the way (1.5 miles) up this trail is another camp. It is located behind a “Closed for Restoration” sign and contains several tree carvings. This site was described in an 1885 account because it represented the closest that campers could get to the rim and still have water readily at hand. From there visitors to Crater Lake would climb another 400 feet over the next mile to reach the high but dry camp sites at what is now a picnic area in Rim Village. The original trail can still be followed between these two points, but careful observation is needed to find the route once it diverges from the upper portion of the modern Dutton Creek Trail. Blazes are still evident at the northwest corner of the picnic area and tree carvings can be seen within a few paces of the Rim Visitor Center. Both furnish silent testimony that the rim attracted people even before facilities were in place to accommodate visitors with automobiles.

The development which has so altered the face of Rim Village is a reminder of how the park’s visitation has changed in the past 100 years. Several thousand people per year came to Crater Lake in the 1890s, but the annual figure is now around a half million. Perhaps more significantly, the average length of visit to the park is considerably different. Whereas the majority of people today spend less than four hours in the park (and far fewer still are here longer than one night), 19th century visitors might spend a week at Crater Lake. They often combined their visit with gathering huckleberries(Vaccinum membranaceum) at Huckleberry Mountain, located just 10 miles southwest of the lake. The wagon road made both places more accessible to white settlers and Klamath Indians, who could afford a respite from the more burdensome aspects of life.5

Travel to Crater Lake has changed a great deal since then, particularly after 1908 when automobiles were allowed in the park. What remains of the wagon road is still important, however, to understanding and appreciating what people once experienced on their journey. Despite being bracketed by modern developments, it can still convey change and continuity to those visitors who seek to better comprehend the past.

An old camp on Dutton Creek. Photo by Steve Mark.

Notes

1 This trail has been marked in several places with commemorative signboards. Perhaps the best preserved stretch is the Sky Lakes Wilderness along what is now known as the Twin Ponds Trail.

2 Led by news editor James Sutton, this group brought the first boat to the lake and used it to explore Wizard Island. They also gave Crater Lake the name by which it is still known.

3 Although the wagon road is heavily eroded in steeper sections and filled with small trees in others, it can be followed to where it crosses Highway 62 about a half mile east of Whitehorse Creek.

4 The relatively short life span of 80 to 120 years for lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta)generally precludes finding blazes on this species, especially since the practice was discouraged after the national park was established.

5 Park founder Will G. Steel recalled seeing more than 200 Klamath encamped near the rim in August 1896. This took place while a considerable number of whites also camped around Crater Lake.