The True Firs of Crater Lake National Park: A Closer Look

Four of the nine species of true fir (Abies) in the United States are native to Crater Lake National Park. Of these, two have been incorrectly identified by some foresters and botanists. There has been no such problem for two other Crater Lake firs: subalpine fir(A. lasiocarpa), and Pacific silver fir (A. amabilis). The problem, rather, has been with trees called “white fir” and “Shasta red fir.”

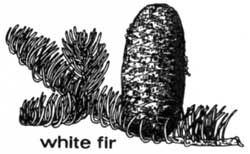

White fir

The term “white fir” has been broadly used to include two identified varieties; Rocky Mountain (“typical”) white fir (A. concolor v. concolor), and the Sierran white fir (A. concolor v. lowiana). The Crater Lake tree is Sierran white fir. This is the park’s lower elevation fir, best seen and appreciated from Highway 62 viewpoints overlooking Castle Creek Canyon toward Medford and along Highway 62 in the “panhandle” toward Klamath Falls.

As is the case along the Cascade Range from central Oregon to the Siskiyous, west slope white firs (especially at lower elevations) integrate with grand fir (A. grandis).Some white firs, just inside the park’s western boundary, show this trend, especially by the coloring of outer bark texture. Outer bark on grand fir, as seen in cross section, has alternating layers of dark brown and violet, while that of both varieties of white fir have softer corky layers of brown and tan. Crown formation, seed cone, and leaf characters are used for separating the two white fir varieties (see Table I).

This species of fir at Crater Lake is best identified as “Sierran” white fir, since some observers may appreciate the varietal distinctions. The Rocky Mountain variety is popularly cultivated as an ornamental throughout much of the northern United States, and is recognized initially by its silvery-blue crown color which resembles that of blue spruce (Picea pungens).

The natural distribution of Rocky Mountain white fir is from the Wasatch and Uinta Mountains south and eastward through Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, eastern Nevada, southeastern California and northern Mexico. Sierran white fir is native to east-central and southwestern Oregon, western Nevada. and in California south to the Tehachapi and San Bernardino Mountains where the two varieties join their ranges and blend morphologically.

Table I

The Basic Differences

| Rocky Mountain White Fir | Sierran White Fir | |

|---|---|---|

| Needles |

|

|

| Cone Bracts |

|

|

| Crown Formation |

|

|

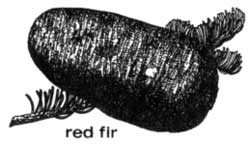

Red Fir

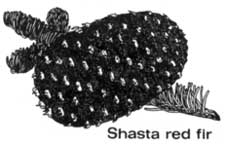

The terms “Shasta red fir” or “Shasta fir” have been used to identify a species of Abies which occurs at higher elevation in the park ever since 1939, when botanist Elmer Applegate wrote that he did not recognize noble fir (A. procera) in the southern Oregon Cascades. His opinion has since had wide influence with foresters, so that the term “Shasta fir” has been used in numerous publications. They have continued to list both Shasta red fir (A. magnifica v. shastensis) and “typical” or “California” red fir (A. magnifica v. magnifica) in southern Oregon.

The type-locality for the variety shastensis is Mount Shasta; for var. magnifica it is the south central Sierra Nevada. Despite the widely-held perception that “typical” red fir is native to Oregon, this variety has not been verified by specimen documentation north of Mount Lassen, where both red fir varieties occur together. The two red fir varieties are morphologically separated by a key seed cone characteristic, that of cone bract length (see Table II). Variety shastensis has bracts (with reduced points) which are exserted beyond the cone scale. In var. magnifica the bracts are shorter, becoming totally hidden within the closed seed cones.

Some foresters have reasoned that “Shasta fir” is the product of introgression between “typical” red fir with hidden bracts, and noble fir with conspicuously-bracted cones. They have established hypothetical red fir boundaries for such “Shasta fir,” with the northern boundary at 44 degrees North Latitude (McKenzie Pass) and the southern boundary in the vicinity of the 41st parallel in northwestern California. This creates a “transition zone” for the “Shasta fir” population, whereby Crater Lake National Park falls inside this zone.

It should be emphasized that noble fir and red fir are closely related, and that studies show them to be highly variable relative to species distinctions based on chemistry, phenology, and morphology. The smooth “Shasta fir” transition zone becomes geographically problematic when the exclusive occurrence of bracted “Shasta” red fir at the southern end of the “typical”‘ red fir habitat is taken into account.

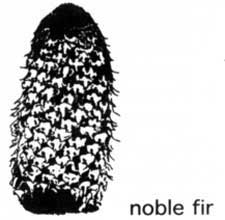

A number of botanists, meanwhile, have recognized noble fir as extending south into northwestern California. The most clearly defined morphological division between noble fir and red fir populations seems to be the Klamath River Basin. The extent of this division (through leaves, cones, progeny development and seedling cotyledon count), is unmatched at any other location in the Cascade Range or Sierra Nevada, greatly exceeding any differences apparent at the “Shasta fir transition zone” boundaries. Although this “Klamath division” follows the southwesterly course of the river to the coast, noble fir has been verified in the Klamath Mountains south of the river. Its absolute southern limit is not yet established, though noble fir-like cones have been collected as far south as Mendocino County (see Table II).

Table II

Noble Fir and Red Fir

Common Characteristics

Leaves flattened four-angle cross-section (rhomboid), blunt or acute, bent at base like a “hockey-stick,” stomatiferous above and below.

Cones large, upright, cylindrical or tapered; light olive-green to dark purplish-brown.

Mature outer bark interior layers of dark brown and deep violet.

| Noble Fir | Red Fir | |

|---|---|---|

| Leaves |

|

|

| Cones |

|

|

| Bark |

|

|

Noble fir and Crater Lake

There is a compelling argument for applying what has been learned about the true geographic range of noble fir within Crater Lake National Park. Even though the bark of some trees in the park resembles the red firs of the Lassen Shasta region, and occasional phenotypes noble fir have cones with rather short Shasta-like bracts, the trees in the Crater Lake vicinity should be interpreted as noble fir. My argument, in summary form, is as follows:

- The established botanical keys for noble fir and red fir identify the common fir north of the Klamath River as noble fir, or at least as a morphological variant of noble fir.

- The name “Shasta red fir” has been borrowed from its original application to the short-bracted red firs of California, and given blanket application to firs in Oregon south of McKenzie Pass.

- The hypothesis that “Shasta fir” in southern Oregon is a “hybrid swarm” or introgressed “transition population” has been weakened by a study which found no evidence of more genetic variability in the so called transition zone than elsewhere.

- Noble fir and red fir are both variable in cone and leaf morphology, and in oleoresin properties (noble fir to a greater degree than red fir). Variability in noble fir is more noticeable in southern Oregon, but variability north of McKenzie Pass has been calibrated, with some of the most extensive differences in resins found near the Columbia River.

- Early botanists named the common southern Oregon species noble fir. It was only later that the awareness of occasional cone and leaf variations suggested relationship to the California firs. This resulted in polarized opinions that have fueled a long-term controversy. Subsequent interpretation of “typical”‘ or “pure” noble fir has produced an arbitrary “north-of-the-McKenzie-theory” which holds that the firs south of that point should not be identified as A. procera. The primary authors of this hypothesis, however, have recently concluded that the classic taxonomic characteristics (cone and leaf morphology) of southern Oregon populations suggested a close relationship to noble fir.

Recognition of the natural variations in noble fir will restore the term “Shasta fir” to its area of origin and intended application. The Lassen-Shasta region has trees with thicker, rougher and more reddish bark than those in southern Oregon. These firs also have larger cones with only partially-exserted or completely hidden bracts, as well as foliage that is anatomically distinguishable from noble fir.

Cones are one of the most commonly used ways to identify trees. The Douglas-fir is not a true fir, as its hyphenated name indicates. Drawing by Hugh Hayes in Trees to Know in Oregon Corvallis: Oregon State University Extension Service, 1995.

References

S.F. Arno and R. P. Hammerly, Northwest Trees. Seattle: The Mountaineers, 1977.

W.B. Critchfield. Hybridization of the California Firs. Forest Science 34:1, 1988, pp. 139-151.

E.L. Parker, The Geographic Overlap of Noble and Red Fir. Forest Science 9:20, 1963, pp. 207-216.

F.C. Sorensen et al., Geographic Variation in Growth and Phenology of Seedlings of theAbies procera – A. magnifica Complex. Forest Ecology and Management 36. 1989, pp. 205-232.

Gene Parker made numerous contributions to the study of botany in southwestern Oregon before his death in 1996. He will be remembered for specializing in true firs, an interest which became the catalyst for several important discoveries in Crater Lake National Park.

Drawings courtesy of U.S. Forest Service, Klamath National Forest.