Wild onion. |

A fellow employee and I once got trapped in a hail storm near Anderson Falls. We found refuge in a small cave along the cliff, but knew that we had to get back to Rim Village. After running back to Rim Drive, a visitor picked us up and took us to the lodge. There were quite a line of cars headed down the mountain, since those visitors did not want to stay around to weather the storm. Very shortly after we reached the lodge, however, the rain stopped. We were the only ones left on the rim, it seemed, and then the clouds began to lift. As if we were the only ones who were meant to see, a rainbow formed and arched low over the lake. It moved across the water to the other side as the storm clouds headed eastward, and washed the rim wall with its colors.

Crater Lake itself seems to have many colors, textures, and moods that change frequently. Though the lake seems to be ever constant, staying the same year after year, one has only to spend a day along its edge to know differently. Some visitors stay for only an hour or two, and of course fail to appreciate the subtle and dramatic changes that take place.

The water is not blue, nor gray, but is crystal clear. Sunlight penetrates the water, some of which is reflected, but most is refracted or bent by the water molecules in the lake. White light from the sun is a blend of all visible wavelengths and penetrates Crater Lake’s surface. Most of the reds and yellows are absorbed in the first few feet of water. The greens that are often seen along the lake’s edge and around Wizard Island reach down further, but become absorbed at relatively shallow depth. Blues reach the deepest, with these wavelengths being scattered and bent. Much of that blue light is reflected toward us. This provides that deep blue as we gaze at the lake. The color of Crater Lake at any one time is influenced by the intensity of sunlight, cloud cover, and suspended particles in the water.

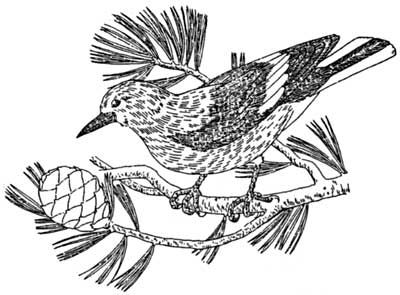

Clark’s nutcracker. Drawing by L. Howard Crawford, 1936.

Sometimes the clouds pour into the caldera, much like water from the spout of a pitcher, reminding one of the witches cauldron in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. The differences in air pressure and temperatures between the caldera and surrounding mountain slopes, often cause clouds to rise or descend. On one occasion, when the clouds poured into the caldera, they descended along the lake surface but left the rim walls and Wizard Island’s conical peak poking out of the blanket. Although park employees knew this was a rare event, some visitors were puzzled and subsequently complained because they came to see the lake, not a bunch of clouds! If only they could understand how special this event was, they might have joined in the excitement.

Along much of the rim you can observe the survival struggle of whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis). Their growth is limited by the slope, aspect, direction and strength of winds or storms, availability of water, and the Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana). The resinous cones are sealed to protect the seeds from most predators, but the Clark’s nutcracker (as its name implies) can break open these cones. It is as though this bird has just the right tool to pick the lock on this safe of seeds. They cache the seeds for their winter food supply, which is usually located along a ridge top where winter winds scour the snow. The bird does not always find its caches, so this eventually results in another crop of whitebark pines! Ornithologists believe that the tree and bird co-evolved, for the tree depends upon the bird to plant its seeds.

Ernest G. Moll, in his collection of poems about Crater Lake, wrote of the whitebark pine:

On this torn ridge he rooted, proud and free,

Battling the wild earth-forces for control;

Life granted not his dream of beauty, so he,

Majestically dying, reached his goal.

Sundew. Drawing by Walter Rivers, 1948. |

Crater Lake is also where I began to learn many of my wildflowers. The glacier lilies (Erythronium grandiflorum) that sprout along the Rim Drive are one of the first flowers to come up through the snow in early summer. Adorning the south facing and drier talus rock slopes are the pasque flowers(Anemone occidentalis). As the flowers fade, the stems grow high above the rocks, pushing the pom pom-like seedheads into the wind. This allows seeds to be dispersed more easily.