Sedges Have Edges

“Sedges have edges; rushes are round; grasses are hollow right up from the ground”1

|

Carex nigricans black alpine sedge single spike |

|

Carex luzulina woodrus sedge cylindricdal spikes |

|

Carex athrostachya slenderbeak sedge dense head of spikes |

The jewel like wet meadows of Crater Lake National Park owe their rich green color largely to a group of grasslike plants, the sedges (the genus Carex in the plant family Cyperaceae). Sedges can be found in many other habitats such as forests, streams, and dry pumice fields. These plants have edges because their stems are triangular rather than being round like grass or rushes. Sometimes the sedge edges are very sharp due to a row of tiny teeth along the stem angles (sedge leaves also have these sawtoothed margins). In fact, the name of the genus Carex derives from the Greek word meaning “cutter.” Sedge leaves grow in three rows, one along each side of the stem, so that looking down on a sedge plant from above you see leaves extending outward in three distinct directions. Grass and rush leaves, by contrast, grow in two rows. Furthermore, sedge stems are solid, not hollow, like grass stems.

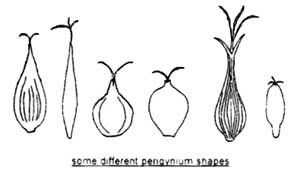

The flowers of sedges are small and appear greatly reduced from the form of familiar wildflowers such as lilies and violets. Sedge flowers have no petals, with each flower possessing either male or female parts but not both. Male flowers consist of three stamens (the pollen-producing structures), whereas female flowers contain the ovary enclosed within a sac-like structure called the perigynium (peri = around, gyn = female, ium = little). Much of sedge identification depends on the size, shape, color, and texture of the perigynia, and looking at these features requires a magnifying lens.

Sedge flowers are borne in dense spikes. Depending on what kind of sedge it is, each spike may contain only male flowers, only female flowers, or both. A few sedge species can have separate male and female plants. Sedge spikes range from short and egg-shaped to long and cylindrical. The arrangement of spikes on the stem usually fits one of the following four general forms: a single spike (only one flowering spike per stem), a dense head (many short spikes per stem, closely crowded into a dense cluster), the “extended head” (a long loose cluster of short spikes), and the “bottlebrush” type. The “bottlebrush” sedges have a few long cylindrical spikes on each flowering stem, and the spikes often look like tiny bottle brushes when the flowers are in full bloom). Three of these types are shown at the beginning of this article.

There are about 40 different species of sedges in Crater Lake National Park, more than for any other genus of vascular plants. Many of these sedges respond vigorously to lower-intensity fire, sprouting and forming dense swards in burnt areas, For example, following surface fire in ponderosa pine forests in the northeast corner of the park, long-stolon sedge (Carex pensylvanica, also known as C. inops) increases in cover. When people talk about the lush “grass” growth in some of the areas burned by the 1988 fires at Yellowstone National Park, they are usually talking about sedges. Such vigorous regrowth is very important in stabilizing denuded soil and in providing food for wildlife where food supply has been reduced. A variety of wildlife relish sedges and rely on them for nutrition; these include waterfowl, small mammals, as well as the charismatic deer and elk.

Sedges are also important to humans. Their strong, tough fibers, sedges were used by American Indians to make cordage, basketry, and mats. Sedges that have creeping underground stems (rhizomes) were an especially important source of fiber for technology, but whole above ground stems and leaves were also twisted into rope. One late 19th century account refers to the use of commercially-made rope for constructing a building in northern Idaho. The rope frayed and broke, so they made a new rope. This one used locally-growing sedges and did not fail.

Many sedge species look alike and learning them involves looking closely at their characteristics. Sedge identification keys rely on having mature perigynia and knowing the growth habit and habitat of the plants. Identifying sedges is a specialized skill, but once the terminology becomes familiar, learning the plants is very enjoyable and intellectually challenging.

| “You pull off the parts, and soon feel your age Chasing them over the microscope stage! You peer through the lenses at all of the bracts And hope your decisions agree with the facts; While your oculist chortles with avid delight |

Notes

1Anonymous

2Excerpts from a poem in H.D. Harrington, How to Identity Grasses and Grasslike Plants (Swallow Press, 1977)

Joy Mastrogiuseppe has specialized in the study of sedges at Washington State University ever since she worked as a seasonal employee at Crater Lake in the 1970s.

Drawing appeared in the September 1937 edition of Nature Notes from Crater Lake.