Studying the Denizens of Tomsandi

In the summer of 1999 I had the opportunity to thoroughly explore large whitebark pine stands in the vicinity of Mount Scott. Aiming my map and compass toward random coordinates led me through drainages, up slopes, and into tree stands that I would have never seen by hiking the trails. The fieldwork for my senior capstone project at Southern Oregon University involved establishing and taking data in permanent plots for monitoring whitebark pine health. Specifically, I was looking for a tree disease called white pine blister rust. Blister rust is caused by the fungus Cronartium ribicola which invades the bark and stem tissues of five-needle pines including whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis), sugar pine (P. lambertiana), and western white pine (P. monticola).Eventually the fungus girdles and kills infected branches and stems and is responsible for the decline of white pines in British Columbia and throughout the United States.

Mount Scott with whitebark pines in the foreground. Parkhurst family photo, ca. 1916.

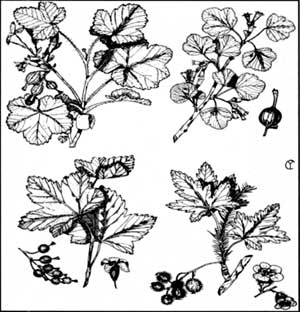

Common species of native currants (Ribes) that occur in Crater Lake National Park. Drawings by Charles F. Yocum in Shrubs of Crater Lake, (Crater Lake Natural History Association, 1964), p. 12. |

In the late 1800’s expanded commercial cutting of white pines increased the demand for seedlings to be planted, but American nurseries could not profitably meet this demand. A high tariff, which had previously limited importation, was removed and large numbers of seedlings were imported from Europe between 1907 and 1909. Species native to North America were grown in the European nurseries and often shipped back infected with blister rust. The fungus is native to Asia and most North American white pine species are highly susceptible even though some natural genetic resistance exists. Blister rust was first found on the East Coast in eastern white pines as early as 1909. It spread quickly because infected seedlings from Germany had been planted throughout the Northeast. This allowed the fungus to spread from the New England states toward Minnesota, and as far down as North Carolina. Discovery of blister rust in western North America came in 1921, but the origin of contaminated seedlings could be traced to a shipment from a French nursery 11 years previously that arrived in Vancouver, British Columbia. Since then, the disease has spread throughout the range of western white pine in California, Oregon, Washington, northern Idaho, western Montana, and northwestern Wyoming.

The fungus has a complex life cycle that includes two hosts, five spore stages, along with strict moisture and temperature requirements. The alternate host requirement means that Cronartium ribicola infects two very different plants. Part of its life cycle depends upon five needle white pines; the other part infects currants and gooseberries of the genus Ribes. Of the five spore stages, two are of major concern in the spread of blister rust. One stage of the life cycle produces aeciospores that develop on pines, are long lived, and can travel considerable distances to infect only Ribes bushes. Amazingly, these types of spores have been known infect Ribes after travelling by wind for over 300 miles, Another stage produces sporidia that develop on Ribes, are short lived, and sensitive to sunlight and moisture conditions. Sporidia can only infect white pines and are capable of spreading infection within a radius of about 900 feet under normal conditions, A period of 48 hours with a maximum temperature of 68 degrees Fahrenheit and moisture-saturated air are necessary for sporidia from the Ribes host to develop, spread to, and infect white pines.