“Lake Majesty” through the Photographer’s Eye

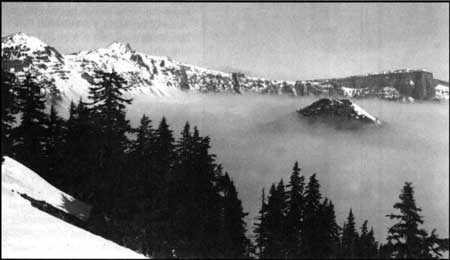

Fog in the caldera late fall 1958. NPS photo.

There is a physical sense of envelopment when standing on the rim of Crater Lake. It is as though one becomes part of the circumference of the lake and you are connected to it like the arms from your shoulders.

Needless to say, the beauty of Crater Lake has drawn some big names in fine art photography over the past century. Both Ansel Adams and Edward Curtis worked at the lake as well as many, many others. For me to find my own artistic voice here was a real challenge. For one thing, the caldera is about six miles across at its widest point and the sheer walls fall one to two thousand feet. It is a HUGE physical space, where all that geometry and scale must be reduced down to a small, two-dimensional picture.

For the fine art photographer, our tool is light. We can use light from the sun to create a sense of geometry in order to represent the presence of what we are photographing. To do so on such a large scale as this lake requires extraordinary light. For me that light typically comes as the first winter storm clears, leaving a fine powder of white snow on the caldera walls. This highlights the geological formations in its volcanic form. The rolling of the storm clouds as they clear create modulating moods, filtering the sun.

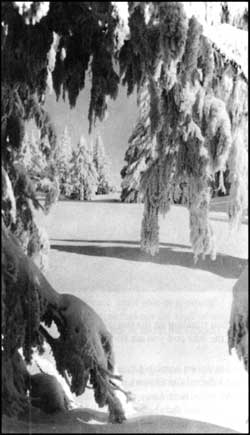

Later on in winter, the annual accumulation of snowfall (44 feet on average) results in less geometry—as more and more of the surfaces are blanketed in white. My hope through this work was to impart a sense of the size, grace, and envelopment that one senses when standing on the caldera’s edge. As two major storms cleared, I made about 300 exposures on the films I carried away from the park. At one point I even used a rock climbing harness and rope, anchoring myself to trees while shooting on the snow covered slopes of the caldera.

Winter scene at Crater Lake, 1931. NPS photo by Rudolph F. Lueck. |

My work has taken me all over the western United States, deep into remote wilderness areas. I have seen and photographed many incredible views of the West and what makes us “Westerners,” but few of my travels have touched me personally as much as this lake. After one discovery by white men in the nineteenth century, it was named “Lake Majesty.” Perhaps that is the most fitting name of all. The sky, its clouds, and the sun’s warmth somehow seem to extend from this lake in awesome majesty as though this was the center of the world. For one brief moment I felt connected to it all and insignificant as its witness.

Did I make an image through the lens of my camera that captures the spirit of this lake? I don’t know yet. At the time of writing, the negatives are still in a drawer. After time has passed and I forget the physical pain associated with taking each shot, I will select my best negatives and the work will begin in earnest. For it is at this stage that I try to coax out a work of art, one that reflects what I saw and felt in my mind’s eye at the time of creating each photograph. I pull the finished work out of the raw negatives, much like a diamond cleaver cuts the jewel from raw stone.

Hopefully you will see the results of my work at Crater Lake as part of the park’s centennial celebration. It has been a great challenge for me and the outcome is uncertain, but what I take away from here in my heart is not. I felt wonderment at having been a part this magnificent place for a brief moment. May you have the same experience.

The author wishes to thank the staff at Crater Lake National Park for their hospitality during his working residency that took place in November 2000. Images by Peter Meyers.

Peter Meyers of Santa Fe, New Mexico, participated in a program facilitated by Southern Oregon University to produce art for the centennial of Crater Lake National Park.