The Crater Lake Currant

From Nature Notes, Vol. VIII, No. 3, Sept. 1935

A shrub limited in distribution to the Cascade Range in southwestern Oregon is the Crater Lake currant (Ribes erythrocarpum). The heart of its distribution is Crater Lake National Park, but this plant is found as far to the west as Rabbit Ears and Huckleberry Mountain, then south to Four Mile Lake near Mount McLoughlin. To the east it occurs on the summit of Yamsay Mountain, a peak located beyond the Klamath Marsh.1

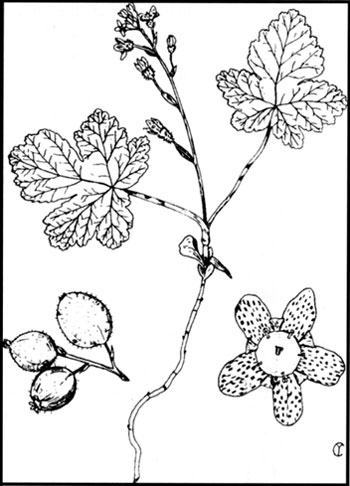

Some plant lists for the park have identified nine species of currants in the genus Ribesto be found within its boundaries. Crater Lake currant is a trailing shrub with copper colored flowers and red berries. This species was first identified and described in 1896 by Frederick Coville and John Leiberg. These men were among the first to make detailed botanical investigations in this part of Oregon. They and others found the Crater Lake currant to be common everywhere in the subalpine areas of the park. It is the dominant shrub in the mountain hemlock forest, where its creeping stems carpet large areas, but is less abundant in the lodgepole pine thickets and infrequent among the whitebark pines that occur near the rim.

Crater Lake currant is interesting because of its limited range, but also because of widespread concern about the ultimate fate of whitebark pine. A pathogen, Cronartium ribicola, was introduced from Europe in the early twentieth century and is commonly known as white pine blister rust. Currants and gooseberries serve as an alternate host of C. ribicola, a fungus that causes white pine blister rust. The rust is not a threat to currants or gooseberries, but it is a very serious disease of five needled pines. North American white (or five needled) pine species include bristlecone, limber, sugar, eastern white, southwestern white, western white, and whitebark. All of these species are highly susceptible to white pine blister rust, a disease that causes significant damage in pine forests by forming cankers on the branches of white pines. These cankers ultimately kill the trees.

The forests of Crater Lake National Park contain several species of the five needled pines: western white pine (Pinus monticola), sugar pine (P. lambertiana), and whitebark pine (P. albicaulis). Western white pine is fairly common at middle elevations and is found scattered among other tree species. Sugar pine is interspersed among ponderosa pine, lodgepole pine and Douglas-fir stands in lower park elevations. Whitebark pine extends from about 6500 feet elevation on East Rim Drive to the top of Mount Scott, at 8,929 feet the highest point in the park. The whitebark pine habitat type is more of an open woodland than a forest and is usually not as interspersed with other species.

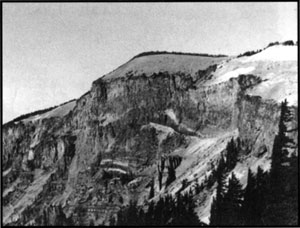

Cloudcap at center Note the whitebark pines lining the ridges. NPS photo by Robert G. Bruce, 1966. |

Whitebark pine is a distinctive and critically important tree of high mountain ecosystems in western North America. Its large nut-like seeds are a high-quality food for several species of birds and mammals. Whitebark pine ecosystems are primary catchment zones for late-lying snow fields, so their condition is important for water quality and watershed protection. This tree species has varied and picturesque growth forms which provides a unique aesthetic experience for human visitors to this high mountain ecosystem. For many years the commonly held solution to white pine blister rust in North America was to eradicate all Ribesspecies. With a massive national campaign launched to save five-needled pines, all currants and gooseberries within identified control areas were targeted for removal. Between 1930 and 1971, 14.3 million native Ribes plants were extirpated from Glacier, Yellowstone, Grand Teton, Rocky Mountain, and Mount Rainier national parks. By 1936 it was evident that white pine blister rust was rapidly approaching Crater Lake National Park. It was determined that protection of the Cloudcap area and its homogeneous stands of whitebark pine was imperative. Accordingly, the Cloudcap Blister Rust Control Unit was established as a cooperative venture with the Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1937. Within three years more than 133,600 alternate host plants (Ribes sp.) were eradicated in a control unit of 3,632 acres.2

Elmer I. Applegate, then curator of the Dudley Herbarium at Stanford University and a seasonal naturalist at Crater Lake, wrote a letter in July 1937 to Park Superintendent David Canfield about the prospective eradication work:

As indicated by Applegate’s 1937 letter, the early effort to control white pine blister rust illuminates a larger issue, that being whether national parks should try to save one native species at the expense of another, or at the risk of environmental contamination. These remain difficult questions since forests at the park still have a component of five needled pines. Although whitebark pine is normally a long-lived tree, in recent decades it has suffered heavy mortality as a result of the white pine blister rust in parts of its range and is now being evaluated. White pine blister rust is found in virtually all areas near Crater Lake with whitebark pine. Surveys found an average infection rate of 52 percent in whitebark pine. Investigations conducted in the immediate vicinity of the park discovered 10 percent mortality among the whitebark, with blister rust being the most frequently encountered cause. The surveyors encountered only one Ribes plant amid the whitebark pines. This indicates white pine blister rust can be carried in the wind for long distances.4

Although whitebark pine is normally a long-lived tree, in recent decades it has suffered heavy mortality as a result of white pine blister rust throughout the Pacific Northwest. Southwestern Oregon and northwestern California have long been recognized to be an area of tremendous biological significance because of the many species and species that are unique to selected areas. The Crater Lake currant is a one of these species that adds to the biological significance of the region, though its management in the park has been interwoven with two of its companions—the five needled pines and Cronartium ribicola, the exotic invader that threatens the riches of the forest.

Crater Lake Currant, Ribes erythrocarpum. Drawing by Charles F. Yocom.

Notes:

1Elmer I. Applegate, “Plants of Crater Lake National Park,” The American Midland Naturalist 22:2 (September 1939, p. 272).

2Crater Lake National Park Master Plan, Development outline, Forest Protection: Tree Disease Control [1941].

3Applegate to Canfield, July 2,1937, copy in Applegate file, Crater Lake National Park.

4Ellen Goheen, et al., the Status of Whitebark Pine Along the Pacific Crest Trail, Umpqua National Forest, Oregon, White Pine Blister Rust Meeting Abstracts, September 1999.

Greg Reddell works for the Bureau of Land Management from its Klamath Falls Resource Area office and has served as president of the Friends of Crater Lake National Park.