Volume 23, 1992

All material courtesy of the National Park Service.These publications can also be found at http://npshistory.com/

Nature Notes is produced by the National Park Service. © 1992

Introduction

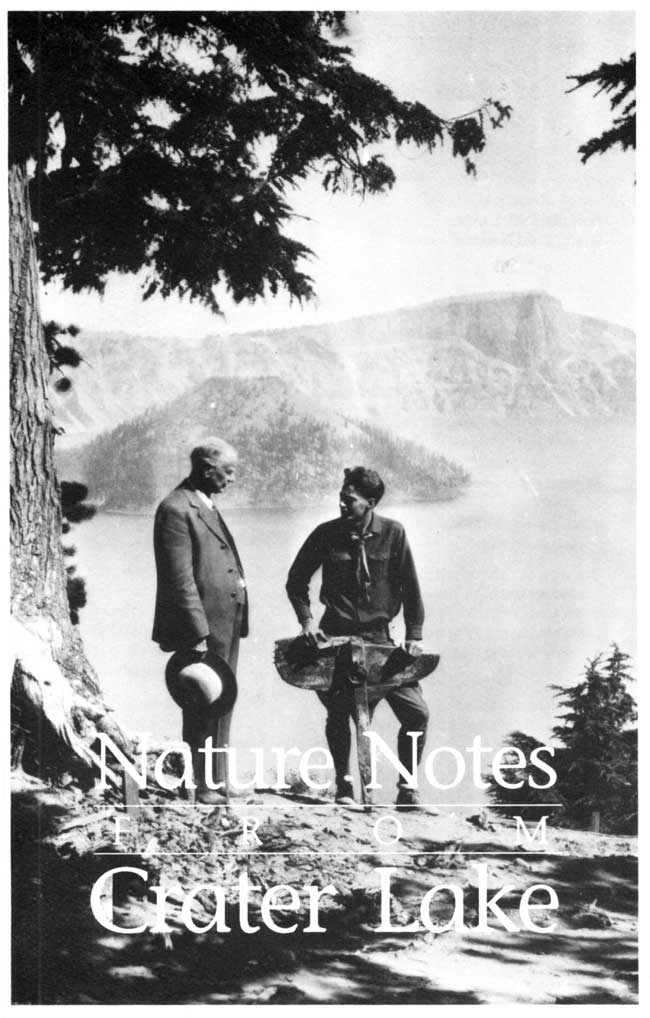

Crater Lake National Park celebrates its 90th anniversary this year. On May 15-17, 1992, the Crater Lake Natural History Association, Southern Oregon State College, and the National Park Service will cosponsor a symposium on the park to celebrate its birthday. The educational opportunity afforded by the event is the impetus behind reviving Nature Notes from Crater Lake.

At one time, most major national parks published their own “Nature Notes”. Nature Notes from Crater Lake were first published in 1928 and twenty two issues followed, with the last publication in 1961. With this issue we hope to stimulate interest in producing future editions. Reprinting Nature Notes articles is encouraged, as long as credit is given to the authors and the Crater Lake Natural History Association.

This volume begins with an article by Lincoln Constance. A seasonal naturalist in 1931 and 1932, Dr. Constance is an emeritus professor of botany at the University of California, Berkeley. Although his piece is an exception to the traditional policy of not using previously published work in Nature Notes, he has graciously allowed us to reprint the article because it sets the stage so well for the other contributors.

It is followed by submissions from permanent park staff, current and former seasonal interpreters, and one by two members of the Crater Lake Natural History Association’s board of directors.

The Crater Lake Natural History Association was established in 1942. Its purpose is to aid the National Park Service in educational, scientific, cultural, historical, and interpretive programs. Toward this end it sponsors this volume of Nature Notes from Crater Lake. The association operates three publication sales outlets, two at Crater Lake National Park and one at the Illinois Valley Visitor Center in Cave Junction, Oregon. Proceeds from sales items are used entirely to support the association’s goals. A list of items for sale can be obtained by writing to the Business Manager, Crater Lake Natural History Association, P.O. Box 157, Crater Lake OR 97604.

| National Park Service Crater Lake National Park  |

Crater Lake Natural History Association  |

| South Oregon State College  |

|

Crater Lake National Park as a Field for Scientific Research

By Lincoln Constance

Cleetwood on Crater Lake, July 1886. Photo courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society.

[This article first appeared in the Oregon Education Journal of February 1932, pp. 26-28. Although we are now 60 years hence, much of what Dr. Constance had to say at that time is still relevant today–Editor.]

As an area of intense scenic beauty and great recreational interest, Crater Lake needs no introduction to the residents of Oregon, nor to the thousands of citizens of other states and nations, who yearly visit it. Every summer an increasing number of people give themselves the pleasure of motoring over the Rim Drive, which completely encircles the lake. The motorboat trips to Wizard Island and the Phantom Ship– one of the most unique water trips to be found anywhere in the world–are being included in the schedules of more and more tourists annually.

Field for Scientific Study

But the thrilling, fascinating beauty of the park is not more important than the manifold fields for scientific investigation which it offers. A greater familiarity with the outstanding features of Crater Lake–the Rim, Wizard Island, the Devil’s Backbone, and many others–leads frequently to a thirst for information of various kinds. In the words of J.S. Diller, geologist of the United States Geological Survey, and one of the pioneers in the geology of Oregon: “Aside from its attractive features, Crater Lake affords one of the most interesting and instructive fields for the study of volcanic geology to be found anywhere in the world.”

Undoubtedly the most interesting problem is the very old one of the method of formation of the caldera in which lies the lake itself. The question was not “settled years ago,” or, at least, it has refused to remain settled.

Two important theories have been formulated to explain the unique position of Crater Lake. These are commonly designated as the Explosion Theory and the Engulfment Theory, respectively. The park area has only once undergone an extended and intensive geological inspection and interpretation, and that was more than a quarter century ago. The last twenty-five years have brought to light many discoveries, which seemed to cast upon, and to verify, the results obtained at that time. The results of the pioneer investigation were published in 1902 by J.S. Diller and H.B. Patton. From their findings, these geologists and petrographers have examined the revealed structures, and these have almost unanimously supported the Explosion Theory. Hence, we find that the most fundamental scientific problem Or Crater Lake still awaits an ultimate solution.

Crater Lake a Geological Laboratory

Crater Lake is a geological laboratory par excellence, for here we find an immense mountain (the hypothetical Mount Mazama) dissected for us, and its core displayed. Here we have revealed to us all the evidence necessary to reconstruct the orogenic processes which formed Mount Mazama, and the clues to the activity of vulcanism and glaciation, which ultimately resulted in its destruction, are likewise exposed. As the Grand Canyon gives an unequalled calendar to the entire history of sedimentary processes upon the North American continent, so Crater Lake Rim exposes the history of the more recent volcanic forces, which so appreciably altered the topography of the Northwest.

from “The Trailside Speaks,” L. Howard Crawford, Nature Notes, Vol. VII, No. 2, August 1934. |

In its capacity as a museum for the preservation of the effects of volcanic and erosive forces, the park possesses many prize exhibits. The most conspicuous is the caldera or basin within which the lake lies. Rising amazingly from this chalice is Wizard Island, a perfect volcano, a child of a secondary outbreak of vulcanism. The alternate layers of lava and of ash which form the substance of the rim, the frosting of pumice upon Cloud Cap and other promontories, the Devil’s Backbone and other dikes, the plugged valleys (Llao Rock and the Palisades), the steam stains, and the widespread bombs, are samples of this colossal display.

Effects of Geological Erosion Manifest

While the fact is not widely appreciated, the existing remnant of old Mount Mazama affords an excellent field for the study of glacial erosion. Kerr Notch and Sun Notch are two of the most typical U- shaped valleys, although there are several others. Glacial deposits are abundant, for the park roads frequently cut through heterogenous morainal material, and the public camp ground is situated upon a terminal moraine. The rapid recession and change in angle of the rim, from an acute to an oblique angle with the lake surface, shows the action of erosional forces still at work, which will not rest until the immense rim is levelled. The presence and position of glacial deposits and cuttings, the lava flows, pumice beds, dikes, and the Like, are the alphabetical blocks which must be assembled to complete the geologic history of this region.

Park Has Other Geological Features

Passing away from the lake itself, we find at least two other classes of interesting geologic features worthy of notice and study. The park contains a large number of volcanic cones: Red Cone, Crater Peak, Timber Crater, Scott Peak, and others. In the case of two such cones–Union Peak and the Rabbit’s Ear–the lava froze in the neck of the mountain. Upon the lower levels of the park confines, there are deposits of ash, pumice, and other ejectema of great depth. Last summer, Mr. D.S. Libby, park naturalist, studied the remains (some twenty miles west of the lake) of large logs, which were buried to a depth of sixty feet beneath ash, apparently from Mount Mazama! This igneous material is most apparent where it has been deeply channeled by the small streams, which have cut impressive canyons through its unresisting substance. Not only water, but wind, also, has lent a hand to erosion, and the finger-like Pinnacles of Wheeler Creek, and the medieval turrets and oriental minarets of Godfrey’s Glen, Castle Creek, etc., are the result of the activity of these combined forces.

Flora and Fauna Abound

The geological interest is paramount, but the possibilities of research are by no means exclusively confined to the geological agencies and their products, for the park represents a teeming and diversified flora and fauna. Although the park contains but two hundred and forty-nine square miles, the enclosed area possesses an imposing array of life-forms. The altitude presents an approximate range of from four thousand five hundred to nine thousand feet.

We recognize that all life is arranged in definite latitudinal and altitudinal bands, or zones. Also, as was first shown by Alexander von Humboldt, the zones of altitude and of latitude correspond. The names are derived geographically rather than altitudinally. In the case of Crater Lake Park, we find the Hudsonian Life Zone, extending from the highest levels to about seven thousand five hundred feet; the Canadian Life Zone, from seven thousand five hundred to five thousand five hundred feet; and below five thousand five hundred feet, the Upper Transition Life Zone, so called because the southern and northern life-forms mingle here indistinguishably.

Each of these life zones possesses its own distinctive representatives of the plant and animal kingdoms, although the segregation is more obvious in the case of the plants than in that of the exceedingly mobile animals.

The larger animals are usually quite shy, but the black bear make the garbage-pits their especial soup- kitchen. Where wind and water have sculptured the ashen walls of the deep canyons, forming caves and over-hanging walls, the deer make their extensive nurseries. Porcupine and marmots are frequently seen, while coyotes are rather rare visitors. On Copeland Creek, several miles to the northwest of the lake, extensive workings of the mountain beaver were discovered this last summer. The small squirrels and chipmunks, especially the Golden-mantled Ground Squirrel, which is usually called a “chipmunk,” are the favorites of the tourists, who seek to exhaust the local supply of peanuts.