Remote But Not Forgotten

Three miles south of Kerr Notch on the Pinnacles Road lies a small campground called Lost Creek. With only 16 sites, it appears to be almost forgotten. But not to a number of park employees who regularly visit Lost Creek during the summer.

pinnacles Illustration by L. Howard Crawford, Nature Notes from Crater Lake, 1934. |

A maintenance worker arrives daily to clean the restrooms and camp area. Sometimes repairs to buildings are required if they are damaged by bears, porcupines, or thoughtless visitors. Maintenance personnel also test the campground’s water system daily to ensure that it meets strict standards.

Park rangers visit Lost Creek all summer to meet the needs of visitors who come to this corner of the park. Many of the rangers participated in a campground revegetation project several years ago that is now adding greatly to the area’s appearance. A number of native trees and shrubs have reduced the visible impact from many years of camping on pumice soils.

From Lost Creek Campground, a dirt road (the Grayback Motor Nature Trail) heads west one way, returning to East Rim Drive at Vidae Falls. In early spring a crew grades the roadway and removes trees that have fallen during the winter months. Sometimes elk, deer, or even an occasional bear with cubs can be seen feeding along this route.

Four miles south of Lost Creek are the Pinnacles. These are fumaroles which served as passageways for gasses escaping from the pumice-scoria flows when Mount Mazama erupted. Although these erosional remnants are found along several other canyons, the Wheeler Creek Pinnacles are the most impressive in the park. A newly constructed wayside exhibit describes in greater detail how these were formed. For the safety of visitors, a new guard rail has been installed because the canyon drops sharply from the road. Like Lost Creek, Wheeler Creek is a forgotten stream that will share many surprises with those who care to explore it.

In Rare Abundance…

A Story of Serendipity and Biogeography

The living biota we enjoy around Crater Lake’s caldera reflects the 7,700 years of change since Mount Mazama’s climactic eruption. Mysteries abound despite our attempts to understand the distributions of plants and animals. Nevertheless, we do know that present-day populations of plants, for example, are a reflection of historic events such as fire, volcanic disturbances, and climatic changes. Thus, in the sense of genetic lineage, contemporary plants are the survivors of many changes critical to sustaining life on Earth. Much attention has been paid to the coniferous forests which dominate the park landscape, yet there are many lesser woody and herbaceous plants whose presence and life stories may go unnoticed.

Besides the many who have scanned the landscape during short visits, the National Park Service has had several capable field botanists who worked toward completing and annotating a Flora for Crater Lake. Elmer Applegate, F. Lyle Wynd, William Baker, and Richard M. Brown would be quick to point out how the gift of finding things not sought for has shaped their work. For a thorough inventory of Crater Lake’s plants to be achieved, we must acknowledge the role of serendipity in botany. Serendipity has led to the realization that some plants are locally rare — that is, in the oxymoronic sense, in rare abundance. Once rare isolated populations have been located, we often find that individuals of the same species are abundant within the boundaries of that small, local population.

As an example of rare abundance, Rick Kirschner wondered in 1978 whether beargrass occurs at Crater Lake. No botanist had collected a voucher specimen for Crater Lake so beargrass was not listed in Crater Lake’s Flora. But I knew that Rick had worked at Mount Rainier National Park, where wildflowers are profuse. I was also aware that Rick knew how to recognize flowering beargrass, Xerophyllum tenax, a member of the Lily Family and not a true grass. Earlier distribution maps of beargrass place it well north, west, and south of the park — but no populations were known to be within its boundaries.

While on backcountry patrol in the northwestern part of the park, Rick thought that he had seen what appeared to be beargrass flowering in the distance but he returned to headquarters without a voucher specimen. Could this be another curiosity reported without evidence, or was it truly an opportunity for discovery? In time we successfully relocated the site to confirm the presence of beargrass at Crater Lake. Of course, the discovery of a small population well inside the park boundaries raised a number of questions: Did the devastation of Mazama’s climactic eruption have anything to do with beargrass distribution? Could it be that 7,700 years ago, a small area shielded by deep snow and harboring beargrass miraculously survived the catastrophe? Did beargrass colonize much more recently?

beargrass David L. Wheeler & Thomas Atzet, Guide to Common Forest Plants, Forest Service, USDA, Pacific Northwest Region, 1985. |

Factors which contribute to the perpetuation of rare plants become critical for park managers who aim to promote and sustain species diversity. Some species are sensitive to severe fire disturbances and may suffer population declines, whereas others may be favored by more moderate fire effects. This may be the case with another member of Crater Lake’s rare plant list, and an object of yet another accidental discovery.

During August 1982, park ranger John White and I collected a plant from the Solanaceae Family thriving in robust colonies on Crater Peak’s southwest slope. Our mission was not collecting plants, but merely to examine the park’s first forest fire area that had been allowed to burn under natural conditions. Following two weeks of variable fire behavior in August 1978, a wet snow extinguished what lightning had ignited. The Good Bye Fire burned old-growth noble/red fir forest, and the changes in habitat and vegetation were dramatic. Having started a fire effects monitoring project, I know this plant did not occur on the site before the fire event. The magic of the “friendly flame” had created a specialized habitat, with the result being what was once rare now is locally abundant.

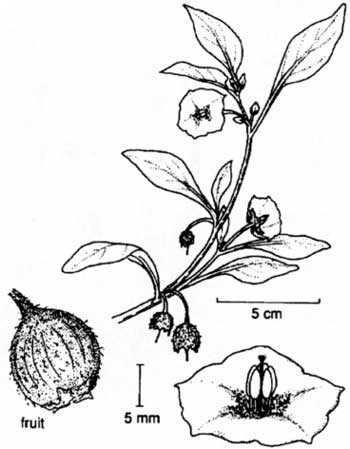

The identity of this member of the Solanaceae (Nightshade) Family turned out to be the rare dwarf nightshade, Chamaesaracha nana. Other family members are more familiar and include such notables as the potato, tomato, tobacco, and pepper. Upon hearing of the dwarf nightshade’s discovery, resource manager Mark Forbes labeled it correctly as a “dwarf tomato.” The fruits are approximately one centimeter in diameter, colored light green, and give the appearance of a miniature green tomato. Although small mammals utilize these fruits, people are advised to avoid consumption until more is known about the tomato’s composition. Like the beargrass example, a number of questions remain unanswered: How did these plants arrive in this place? Where was the plentiful seed source to account for such a proliferation of dwarf nightshade colonies? Could it be that the seeds lay buried within the volcanic soils, remaining viable for many decades and awaiting a fire event?

dwarf tomato

James C. Hickman, The Jepson Manual, Higher Plants of California, University of California, Berkeley & Los Angeles, CA, 1993, p. 1075.