CLUSTER ARRANGEMENT AND STRUCTURES

|

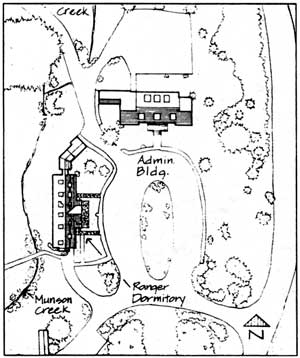

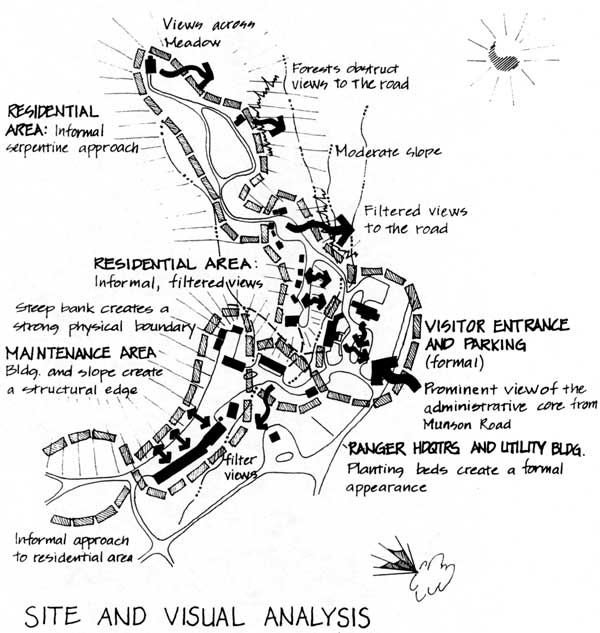

NPS Government Camp, 1939 |

The structural complexes of government camp – administrative, residential, and utility (maintenance) areas – included 36 structures sited in a generally crescent shaped arrangement within Munson Valley. Overall, structures were oriented on a north-south axis, however, east-west orientation of the Administration Building, messhall and warehouse formed distinct building clusters. In the center of the site, the Ranger Dormitory and Administration Building faced the elliptical plaza, creating a sense of enclosure and defining the public spaces of the site. West and south of the plaza several utility buildings were sited at the edge of a paved maintenance work area. On the south end of the site the Sleepy Hollow cabins were aligned on various axes and grouped at the base of the slope.

With the exception of the Sleepy Hollow cabins redevelopment and expansion of the maintenance area, structural clusters remain basically the same. The oil and gas house was removed and replaced by a large covered maintenance building on the east side of the maintenance yard in 1955. The concessioner service and comfort stations once located south of Munson road to the Rim were moved to the north side of the road in 1958.

|

|

Sleepy Hollow cabins, c.1930 (cabins removed in 1989). |

Munson Valley Historic District, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1988, extends south from the Superintendent’s residence (which was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1987) and ends at the maintenance area warehouse. Structures contributing to the rustic theme of the district, totaling 18, were built between 1926 and 1949, and include the Naturalist’s Residence, the middle cluster of residential cabins, the lower cabins, the Administration Building, Ranger Dormitory, Transformer Building, Comfort Station, Mess Hall, Warehouse, and Machine Shop. The Oil and Gas House was removed in 1990.

CIRCULATION

|

NPS Government Camp, 1939 |

The circulation system at Munson Valley has remained relatively unchanged since the design development of Government Camp began in the 1930’s. Primary vehicular access to Park Headquarters is from Munson road between Highway 62 and Rim Village. Secondary roads run north-south connecting housing areas to the administrative core. Located at the center of the district is a circular drive and plaza serving the Administration Building and Ranger Dormitory (the Visitor Center or Steel Building). Leading northwest from the central plaza, a winding one lane road, known as Sleepy Hollow road, rises approximately 160 feet to its terminus at the Superintendent’s residence. Along this road, limited access is provided to other employee residences sited along this road. The spur road access to these residences is known as Stone Houses Road. A second road runs southwest from the plaza, crossing Munson Creek, and widens to a large work area which serves as the maintenance yard. The road narrows beyond the maintenance group and intersects with a secondary site entrance and the Sleepy Hollow area. Pedestrian trails cross Munson Creek, leading north from the Ranger Dormitory to the employee residences, and to the Lady of the Woods. Access to Castle Creek Trail is located southeast across the road at the main site entrance. A bridle trail to Rim Village starts at Sleepy Hollow and runs close to the Superintendent’s residence before switching back along Munson Ridge and north to the Rim.

|

Sleepy Hollow and maintenance area intersection Munson Road intersection at center back. Trail to the middle group of residences and stone bridge crossing Munson Creek west of the Ranger Dormitory. |

Park Headquarters, 1941-1990 |

Access road north to the Superintendent’s residence |

Access road south to the Naturalist’s residence |

SMALL-SCALE ELEMENTS

SIGNS

|

Mission 66 directional sign, routed wood painted brown with creme white lettering |

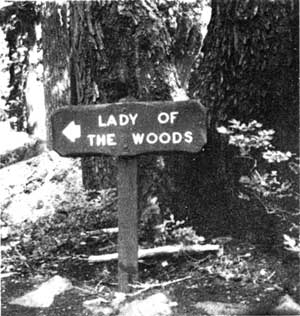

A rustic sign program directed by Francis Lange using CCC labor, began in 1936 replacing many standardized metal signs in the park. A directional sign placed in the ellipse of the headquarters plaza near the road entrance was supported by cut, unpeeled cedar logs. Most probably, the sign was a large four-foot diameter circular slab of oil-impregnated pine with yellow-orange painted raised lettering on a brown background for increased visibility. Signs were designed to be dismantled and stored over winter to prevent cracking of the enamel lettering through wood expansion. Extant rustic wood signs on site are at the Lady of the Woods and the Warehouse. Rustic signs at Munson Valley gave way to routed wood signs painted brown with creme white lettering, as of Mission 66 (1956-1966) improvement programs. Today, few Mission 66 signs are extant with the exception of building and identification signs. Standard metal reflecting signs for traffic are common on site. Other sign types found on site include interpretive, identification of natural features, trails, directional and boundary.

STONE FEATURES

|

|

Flagstone paving detail |

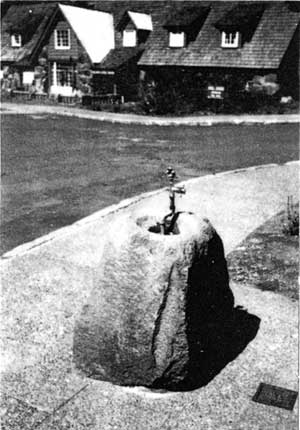

Battered or “rusticated” stone features were a functional, harmonizing element of the Munson Valley landscape. Designed to stand alone yet fit visually into the landscape, stone features provided definition and organization to circulation and plantings. Features at the Administrative complex include stone curbing and a drinking fountain in front of the Administration Building. Other features include a stone bridge over Munson Creek, stone steps between the Ranger Dormitory and the lower cottages, masonry work to hide culverts where the roads crossed the creek, and flagstone walkways at several buildings. Weathered boulders once used for visual effect and to control traffic along the 1934 entrance to the Administrative complex are extant and visible among the plantings south of the ellipse.

|

Drinking fountain in front of the Administration Building |

Stone steps to the lower group of employee residences |

LADY OF THE WOODS

Carved by Earl Russell Bush in 1917, the sculpture stands approximately three feet high and is located 400 feet west of the Ranger Dormitory. A rustic wood sign identifies the site which can be reached by trail from the plaza area.

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

The Munson Valley Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1988 as part of a multiple resource nomination for Crater Lake National Park. The following statement of significance and integrity draws on information from the National Register nomination form, a Historic American Building Survey report documenting the district, and the “Analysis and Evaluation” section of this document.

Although Crater Lake was established as the nation’s sixth national park in 1902, development of an administrative headquarters for the park did not occur until 1926. During this time, a camp located in upper Munson Valley and used by the Corps road crews, gained increased use as summer headquarters for National Park Service employees. Over the next fifteen years at the Government Camp site, the park embarked on one of the most ambitious rustic architecture programs ever undertaken by the National Park Service. Designers transformed an open landscape of infertile pumice soils into an administrative complex comprised of three distinct areas of use. Native stone building construction, use of indigenous plant materials, and careful siting of structures resulted in a highly manipulated designed landscape that was “naturalistic” in character.

Landscape architects Thomas Vint, Merel Sager, and Francis Lange were key practitioners of the Rustic style and influential in shaping the Munson Valley landscape. Their drawings, photographs, and monthly project completion reports provide a wealth of detailed formation about the site’s development and insight into the philosophy of non-intrusive design known as Rustic. Landscape architects Sager and Lange directed general construction and landscape work on the site using Civilian Conservation Corps and Emergency Conservation Work crews. Their responsibilities were far-reaching ranging from design and construction supervision of trails and grading, and finishing portions of Rim Drive, to supervising major construction projects at the Rim and Munson Valley. The park’s “naturalization” program, instituted by Sager, was implemented throughout the park, creating a consistent and cohesive appearance in all the developed areas. Lange continued implementation of the program through additional planting and maintenance of those materials.

By 1941, the Munson Valley area was “home to the most concentrated and coherent expression of Rustic Architecture in the park.” The structures and related landscape formed one of the most extensive developments ever undertaken by the Park Service using this type of naturalistic design.(5)

The Munson Valley Historic District, designed and built between 1926-1941, is significant as a historic designed landscape under National Register Criterion A: for its association with events that made significant contributions to the broad patterns of history; under Criterion B: for its association with the lives of persons significant in our past; under Criterion C: for the distinctive characteristics of a type, period or method of design; and under Criterion D: for the important historic information the site has yielded and is likely to yield.

CRITERION A:

Munson Valley is integrally linked to efforts by the National Park Service to develop, manage and protect the natural recreational resources of one of our oldest national parks. Extant landform and major features, such as stone curbing, trails and roads both contribute to the rustic character of the district. Enough components of the designed landscape survive to demonstrate the nature of park planning and construction of the rustic idiom developed during the late 1920’s and 1930’s which strove to tie rustic-style buildings to their environment. Landscape design development and construction of park headquarters by PWA and CCC crews is representative of a major expansion period in the National Park System made possible under the Hoover administration in the early 1930’s and by the New Deal public works programs.

CRITERION B:

The comprehensive expression of Rustic architecture and naturalistic design principles at Munson Valley is in large part due to the early site planning and design development directed by three NPS landscape architects, Thomas Vint, Merel Sager and Francis Lange. Under Vint’s direction and influence as chief landscape architect, the Rustic Style and its associated design ethic was brought into national parks throughout the system. Vint was specifically responsible for planning the developed areas in the western national parks and monuments. At Munson Valley early development of Rustic architecture is demonstrated by the extant warehouse, constructed as a result of Vint’s 1925 plan for a summer headquarters.

Vint hired Merel Sager to prepare and implement NPS plans for western parks, including Sequoia, Lassen and Crater Lake National Parks. Incorporating the tenets of the Rustic Style, Sager coordinated and directed the construction of large developments at Rim Village and Park Headquarters. Massive boulder construction of headquarters structures characterize the work of Sager, who also oversaw the revegetation and siting of structures and trails. Sager’s work provides a design link between developed areas within the park and other parks in the region, including Oregon Caves National Monument. After Sager’s direct supervision of Crater Lake construction ceased, his National Park Service career (1928-1953) included a term as chief of Park Planning in National Capitol Parks and as chief landscape architect for the overall park system.

Francis Lange, who began as Sager’s assistant and continued as resident landscape architect in the park from 1934 to 1940, had significant impact on the appearance of Park Headquarters. Using PWA and CCC workers, Lange continued the planting program implemented by Sager; designed detail site features and most of the site’s now non-extant rustic signs; and began efforts to better adapt Munson Valley structures to winter conditions. Under Lange’s direction the designed landscape of Munson Valley Historic District was virtually completed.

CRITERION C:

The designed landscape of Munson Valley is significant nationally as an expression of naturalistic design developed and employed by the National Park Service from the mid-1920’s to the early 1940’s. The style, commonly referred to as the Rustic Style or NPS Rustic, influenced state park systems and national forests throughout the country. In western mountain parks, buildings were constructed of native materials and incorporated local colors, shapes, and textures: building forms were designed to suit local conditions and environments, and were sited to blend into the surrounding landscape. At Munson Valley, larger site planning efforts and design detailing successfully blend the overall physical development with the natural setting. Principle features of the designed landscape at Munson Valley are: structures sited against a forest backdrop with the appearance of little disturbance to the natural topography, and the economic as well as aesthetic use of native plant materials to present a highly naturalistic looking landscape in terms of massing and grouping. Enhancement and development of views meld key concepts of the Rustic style and naturalistic design into a cohesive landscape composition.

CRITERION D:

The Munson Valley landscape yields important information about the precepts of naturalistic planting design theory and practice as used at Crater Lake National Park. Landscape features of the administrative complex and Superintendent’s Residence include spatial organization, site plan, views and visual character all of which remain largely undisturbed. These resources contribute significant information relating to estate (residential) planning concepts prevalent in the 1930’s. In addition, the use of native plant materials and natural groupings, and the materials, colors and textures of structures contribute information relating to naturalistic design principles as part of the rustic idiom developed in national parks.

The historic designed landscape of the Munson Valley Historic District possesses integrity of:

Location: The primary structures defining the administrative, maintenance and residential complexes at Munson Valley, including the buildings, circulation system, and vegetation (canopy cover), are in their original location.

Design: The original spatial organization for this site, including land use functions (residential/administration/maintenance) and activities is intact. Though many plant materials have been lost over the years due to natural processes and/or lack of maintenance, the framework of the original planting scheme is still evident.

Setting: The landscape surrounding the Munson Valley Historic District remains virtually intact. From Rim Drive the administrative complex remains visually prominent, and the district’s mature forest continues to screen the maintenance and residential structures from the public. The Steel Circle employee housing development, built in the 1960’s south of the historic district, is physically separate and does not visually impact the main site. Views to Garfield Peak from the Superintendent’s Residence and other areas within the site remain unobscured.

Materials: With the exceptions of snow tunnel additions to the Administration Building and the Ranger Dormitory, and replacement in-kind of building materials during a recent rehabilitation project, structures in Munson Valley remain intact. Existing plant materials are compatible with the historic site although the original plantings are in remnant condition at best.

Workmanship: The buildings of the Munson Valley district are an excellent example of rustic architecture in the park, and represent one of the National Park Service’s most ambitious development programs using naturalistic design to guide the improvements.

Feeling: The historic district possesses a distinct presence within the greater landscape context, evoking a sense of the era in which it was designed and created through its buildings, structures, circulation system, materials and organization.

Association: Munson Valley continues to function as it did historically, as headquarters for Crater Lake National Park. The historic district continues to reflect its associations with the CCC and the Rustic Style of design through its buildings, structures, circulation system, materials and organization.

RECOMMENDATIONS

|

|

Entrance view of the administrative plaza from Munson Road |

Recommendations for the historic landscape at Park Headquarters at Munson Valley are based on an analysis and evaluation of significant historic landscape features and components identified in this report. The purpose of the recommendations is to provide an appropriate framework and programmatic basis for preservation, maintenance and interpretation of the historic site. The historic site as defined in this study includes employee residential areas, the administration buildings and maintenance areas.

The recommendations serve as guidelines and address issues surrounding stabilization and preservation of significant historic resources, removal of non-historic components that compromise the historic scene, and enhancement or reestablishment of historic features as part of a design program for the site as a whole. The six program areas are:

Maintenance and Management Concepts

Buildings and Structures

Circulation

Vegetation

Site Details and Materials

Special Site Areas

MAINTENANCE AND MANAGEMENT CONCEPTS

|

|

West flagstone walkway at the Superintendent’s Residence |

1. It is important to retain the integrity of the historic landscape at Munson Valley by protecting the general canopy cover, viewsheds, and building and circulation layout. These land patterns and relationships define the historic context of the site and contribute to the historic scene. It is important to maintain “a commanding view” of the administrative complex upon arrival to the site (Lange, 1932). The view corridor to the administrative plaza from the road should remain unobstructed and other areas adequately screened.

2. All modern intrusions such as above ground utilities, maintenance structures, and service areas that conflict with the historic scene should be screened or ideally removed. Future intrusions on the site should be avoided, but if necessary, should be appropriate in scale, color, and mass and adequately screened. (See Building and Structures Recommendation #2.)

3. Additional site work is necessary to identify and document existing and remnant plant materials and stonework to verify location, design, function, condition, and maintenance requirements.

|

| Utility box at the middle group of employee residences |

4. Based on recommendations in this document concerning the plaza area and Superintendent’s Residence, Treatment Guidelines should be developed to address maintenance issues common to both sites involving one or more of the following: replacement of plant materials; appropriate construction details; and general maintenance practices for the grounds. These guidelines should be generated by the Cultural Resources Division in collaboration with Park staff.

5. An overall site design and specifications for the historic landscape should be developed for the site. Upon completion of this plan, a comprehensive maintenance plan should be developed according to the conditions outlined under item four.

BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES

1. All historic structures on site within the historic district should be preserved and maintained under an approved cyclic maintenance preservation program. All significant structural resources should be incorporated into the Maintenance Management System, and the Inventory Condition Assessment Program (ICAP), including the Superintendent’s Residence, Administration Building, and Ranger Dormitory.

|

|

Remnant stone curbing around the ellipse and plaza area |

2. Propane tanks sited in front of the employee residences are inappropriate and negatively impact the historic landscape. Burial, relocation or removal of the tanks is required.

3. No new structures should be sited in the historic district or in view corridors surrounding the district. If new structures are required, they should be compatible in siting, orientation, texture, color and materials to existing structures.

CIRCULATION AND ACCESS

VEHICULAR

1. The administrative plaza should remain the main visitor arrival point. Visitor parking should remain concentrated in the plaza area. Employees should continue to use the parking lot north of the Administration Building.

2. Altering the width or character of historic roads is strongly discouraged. New roads should not be added to the site without careful consideration of the potential visual and physical impact to the historic site.

3. The condition of remnant stone curbing throughout the plaza area should be assessed to determine an appropriate strategy for rehabilitation or replacement as noted under the maintenance and management recommendations.

|

|

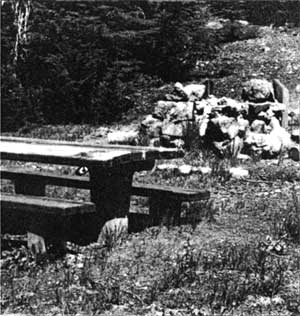

Picnic table and stone fireplace at the Superintendent’s Residence |

4. Reestablishment of stone curbing surrounding the planted “island” between the Mess Hall and Warehouse should be considered.

5. Bicycle parking should be provided in the plaza parking area and in the parking lot north of the Administration Building.

PEDESTRIAN

1. Retain original circulation patterns.

2. The condition of all flagstone walkways, stone steps and the Munson Creek bridge should be assessed and an appropriate maintenance strategy for stabilization and preservation determined as noted under the maintenance and management recommendations.

3. Random paths that cut across the ellipse in the plaza and in front of the Ranger Dormitory, and Administration Building negatively impact vegetation and should be discouraged. Plantings should be reestablished as a way to discourage the development of random paths.

VEGETATION

|

|

Parking lot north of the Administration Building |

1. Additional research is recommended to determine if recommendations for plant maintenance were made with the original design and, when appropriate, those guidelines should be incorporated into new guidelines. A maintenance plan should be developed for the site incorporating those recommendations as appropriate. All landscape maintenance guidelines should be integrated into the Maintenance Management System, and Inventory Condition Assessment Program (ICAP).

2. Selective clearing and removal of plant materials currently obstructing views or undermining the integrity of historic structures should be removed after consultation with the regional historical landscape architect.

3. All new plant materials used at the site to replace materials in poor condition or to reestablish plantings that are no longer evident should be selected from the plant list on page 18.

SITE DETAILS AND MATERIALS

|

|

Planting “island” between the Messhall and Warehouse |

1. Site furnishings (light fixtures, garbage cans, bike racks, signs and interpretive displays) should be visually compatible with the identified elements of the rustic style including scale, texture, and the general site character of Munson Valley. Furnishings should meet all applicable codes and regulations. Complementary design rather than replication is the preferred treatment for rehabilitation and/or replacement of site features.

2. Signs

a. An overall sign for the site plan should he developed based on a hierarchy of style and type of information required. The plan should be consistent with the park-wide plan and should address the possibility of reestablishing Rustic style signs at the administrative complex.

|

Extant boulders once used as a traffic control device for the old entrance to the plaza |

3. Stone Features

a. The condition of remnant stone features should be assessed in collaboration with the regional historical architect and historical landscape architect to determine an appropriate strategy for stabilization and maintenance, including cleaning and clearing of vegetation to enhance visibility as noted under the maintenance and management recommendations.

4. Lady-of-the-Woods

a. Maintain adequate trail access to the sculpture.

b. Replacement of the Mission 66 routed sign with a rustic wood sign should be considered.

c. Routine cleaning of the sculpture should be included within the cyclic maintenance preservation program.

SPECIAL SITE AREAS

|

| Administrative plaza, plan view |

The historic designed landscape of the Administrative complex and Superintendent’s residence, respectively, possess moderate to high integrity of the characteristics that shaped the sites during the historic period, 1924-1941. Composite qualities of integrity – location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association – reflect the spatial organization, physical components, and historic associations attained during the period of significance. While structures of the administrative complex are keystone representatives of NPS Rustic, loss of plant materials and site details present an incomplete picture of the naturalistic design idiom. The designed landscape of the Superintendent’s residence is relatively intact. However, natural processes and lack of a preservation maintenance plan at both areas will adversely impact the degree of historic integrity. Based upon the framework for preservation maintenance defined in the recommendations section, alternative treatments are provided to address issues of stabilization and preservation of these significant historic resources

ADMINISTRATIVE COMPLEX

|

| Remnant plant materials, 1990 |

Since the establishment of Munson Valley as the headquarters for U.S. Army Corps of Engineer road crews in 1913, the plaza area has been a focal point for development. Development of Government Camp took “advantage of topography and forest screening to place out of sight almost every building that is not of direct concern to the visitor.”(6) The only buildings planned to be in sight were the Administration Building and Ranger Dormitory. Today, six structures compose the complex, the most prominent being the Mess Hall (Canfield Bldg.), the Ranger Dormitory (Steel Center) and the Administration Building (Sager Bldg.). Located near the Mess Hall are three other buildings that are part of this cluster, including two comfort stations and a meat house.

Construction of the ellipse and circular drive in 1934 formally established the plaza as the main visitor contact point. Adaptation of the site for winter use and closure of the south entrance brought some change in design and the loss of several small-scale design elements. The plaza, however, stands as a coherent example of rustic architecture and naturalistic design. The composition and relationship between buildings and plant materials, scale, and symmetry suggest a semblance of order and unity with the natural surroundings. The asymmetrical Ranger Dormitory, a balance of two irregular structural masses, is located at the western edge of the plaza. In contrast, the symmetrical Administration Building balances equal structural masses around a central axis and frames the north side of the plaza. These structures, along with the overall layout and organization of the plaza, create a somewhat formal and structured landscape. The plaza area as a whole clearly articulates one of Lange’s design principles that “…government units [should be set] on high points of land for a commanding view.”

|

| Mess Hall (Canfield Building) |

TREATMENT ALTERNATIVES

1. No action/maintenance or status quo:

continue existing maintenance programs for features including maintenance of the historic site through preservation of the view corridor between the administrative plaza and Munson road. Preservation of this view corridor is essential to the design intent and integrity of the original plan and should be retained.

2. Enhance the historic landscape through reestablishment or landscape features:

prepare a cultural landscape report to assess and evaluate all historic landscape features and patterns, and to determine historic integrity and site functions. Integrate historic and contemporary site issues to develop and implement a restorative restoration planting plan. The plan should employ naturalistic design principles described in 1929-38 park documents, including tree placement to create shadows, and the general placement of native plant materials in natural groupings and associations. Prepare a preservation maintenance plan with recommendations for stabilization of remnant plant materials, routine and winter maintenance considerations.

ADMINISTRATIVE COMPLEX STRUCTURES

Administration Building (Merl S. Sager Building)

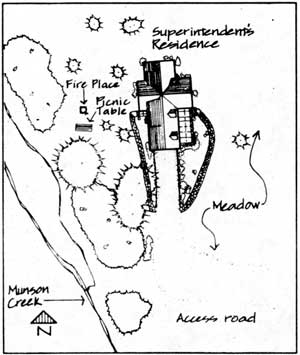

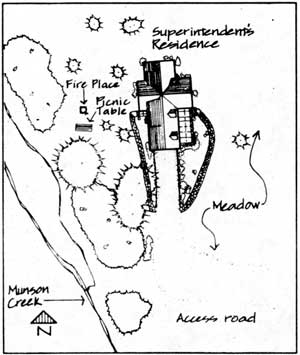

SUPERINTENDENT’S RESIDENCE

|

| Superintendent’s Residence, plan view |

In 1932 Merel Sager described the Superintendent’s Residence as “… one of the most attractive residences in the National Park Service.”(8) In terms of site planning and use of plant materials, period design principles for estate (residential) planning were employed. Located on a knoll at the extreme north end of the headquarters district “… a magnificent view towards the slopes of Garfield [Peak]” was possible from the site. Considerable “groups of [adjacent] hemlock…” provided an effective framing device so that shade and shadow would augment an asymmetrical appearance. “The location is also nicely screened from the road, it being only possible to get a very occasional glimpse of the building as one travels the main highway.”(9)

The structure, built of massive stone masonry using the techniques developed by Sager, relied upon elements of form and scale to harmonize with the natural environment. Still evident are foundation plantings such as twinberry, spirea, Scouler’s willow, and mountain ash installed by Civilian Conservation Corps crews as part of the 1932-34 “naturalization” program. Flagstone walkways provide “formal” access and control foot traffic from the parking area to the residence. A large rolling meadow east of the house is also a fundamental element of the site. Suggesting openness and freedom, the character of the meadow allowed the distant view to be part of the site, expanding the sense of natural setting and context.

|

| Superintendent’s Residence, southeast view |

Today, the relatively unaltered residence and site is an exquisite example of rustic architecture and naturalistic design, and has been designated a National Historic Landmark. Physical history of the district and documentation by the Historic American Building Survey provides evidence that the designed landscape of the residence may merit comparable recognition as a cultural landscape. Current use as seasonal housing and increased visitor use heightens the need for preservation management to mitigate any loss of landscape integrity.

TREATMENT ALTERNATIVES

1. No action/maintenance or status quo: continue existing maintenance programs for features including maintenance of the spatial and visual character of the meadow. Preservation of the view corridor to Garfield Peak and between the residence and Rim Drive access road is essential to the design intent and integrity of the original plan.

|

|

National Historic Landmark plaque for Superintendent’s Residence |

2. Enhance the historic landscape through reestablishment of historic features: prepare a cultural landscape report to assess and evaluate all historic landscape features and patterns, and to determine historic integrity and site functions. Integrate historic and contemporary site issues to develop and implement a restoration planting plan. The plan should employ naturalistic design principles described in 1929-38 park documents including tree placement to create shadows, and the general placement of native plant materials in natural groupings and associations. Prepare a preservation maintenance plan with recommendations for stabilization of remnant plant materials, routine and winter maintenance considerations.

NOTES

|

Access road and meadow at Superintendent’s Residence, looking northwest |

1. Portland Oregonian, August 28, 1921, sec. 4 p.7, quoted in Richard M. Brown, “The Lady of the Woods Revisited”, Crater Lake Nature Notes XXI (1955), 11 in Munson Valley’s Designed Landscape, 1990, 5.

2. General Scheme, Development Program, Crater Lake National Park, n.a. [Charles G. Thompson, Superintendent] Medford, Oregon, January 1928, RG79, 67A614, Box 8936, File 600-03-01 Development Outline, FRC Seattle in Munson Valley’s Designed Landscape, 9.

3. Hubbard, Henry Vincent and Theodora Kimball. An Introduction to the Study of Landscape Design. New York: MacMillan Co., 1929, 267.

4. Mark, Stephen. Notes from an Oral History Interview with Francis Lange, February 1, 1991.

5. Mark, Stephen. Munson Valley’s Designed Landscape. Historic American Building Survey No. OR-144, 1990, 1.

6. General Scheme, Development Program, Crater Lake National Park, 1928, ibid., 9.

7. Lange, Francis G. A Tourist Center in a National Park. St. Louis: Washington University, unpublished Master’s thesis, 1932, 128.

8. Merel Sager to the Chief Landscape Architect, 11-30 July 1932, National Park Service Records, RG79, Landscape Architects’ Reports to the Chief Architect through the Superintendent, Box 1 Crater Lake National Park 1929-34,” National Archives and Records Center, San Bruno, CA.

9. Ibid.

REFERENCES

Crater Lake National Park Interpretation Division files, historic photographs.

“Crater Lake National Park Munson Valley” by Kurt Klimt, 1989, three sheets, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service.

“Crater Lake National Park and Vicinity, OR,” U.S. Geological Survey, 26×25 minute series, 1956.

|

Flagstone walkway, Superintendent’s Residence, west entrance |

Gilbert, Cathy A. and Gretchen A. Luxenberg. The Rustic Landscape of Rim Village, 1927-1941, Crater Lake National Park. Seattle, WA: Pacific Northwest Region, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1990.

Good, Albert H. Park and Recreation Structures, Parts I-III. Boulder, CO: Graybooks, 1990 Reprint of the Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1938.

Greene, Linda W. Historic Resource Study, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. Denver, CO: Denver Service Center, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1984.

Hubbard, Henry Vincent and Theodora Kimball. An Introduction to the Study of Landscape Design. New York MacMillan Co., 1929.

Lange, Francis. G. A Tourist Center in a National Park. Washington University, St. Louis, 1932. Unpublished Master’s thesis.

Lange, Francis G. Interviews with Crater Lake National Park Historian Stephen R. Mark. Vacaville, California, August 1987; 12-14 September 1988; 28 December 1990; 1 February 1991. Typed field notes on file in park.

Mark, Stephen. Munson Valley’s Designed Landscape. Historic American Building Survey No. OR-144, 1990.

|

Superintendent’s Residence, east entrance |

“Munson Valley, Crater Lake National Park, topography”, 1984, drawing no. 106-41025, ten sheets, National Park Service.

“Munson Valley Historic District”, National Register of Historic Places registration form, 1988.

San Bruno, California. National Archives and Records Center. Record Group 79, Records of the National Park Service, Landscape Architect’s Monthly Narrative Reports, 1929-1938. Copies on file in the PNRO Cultural resources Division.

Seattle, Washington. National Archives and Records Center. Record Group 79, Records of the National Park Service, Crater lake National Park.

Shiltgen, Lora. “Managing a Rustic Legacy: A Historic Landscape Study and Management Plan for Longmire Springs Historic District, Mount Rainier National Park.” Master’s thesis, University of Oregon, 1986.

Shiltgen, Lora Ed. Munson Valley, Crater Lake National Park: A manual for Preservation, Redevelopment, Adaptive Use and Interpretation. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon, 1984.

“The Master Plan, Crater Lake National Park” coordinated by the Branch of Plans and Design [drawn by Francis G. Lange], 1939-40, nineteen sheets, Library Collection, Crater Lake.

Tweed, William C. and Laura E. Souliere, Henry G. Law. National Park Service Rustic Architecture: 1916-1942. San Francisco, CA: National Park Service, 1977.

APPENDIX A: CASTLE CREST WILDFLOWER TRAIL

CONTEXT

Physiographic

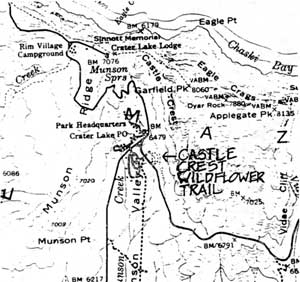

|

| Crater Lake National Park and Vicinity, USGS Map, 1956. Scale = 1:62,500 |

Castle Crest Wildflower Trail is located southeast of the Administrative plaza on the east edge of Munson Valley, at a toe slope of Castle Crest Ridge. A branch of Munson Creek begins at the north portion of the site and runs south, eventually joining the main creek tributary.

Cultural and Political

The Castle Crest Wildflower Trail, originally known as the Castle Crest Wildflower Garden or Nature Trail, is accessible via footpath southeast of the main entrance to the Administrative plaza. Access is also possible from Rim Drive eastbound towards Vidae Falls. This portion of Rim Drive creates the south boundary of the garden area. The property is owned and managed by the National Park Service.

HISTORIC SIGNIFICANCE

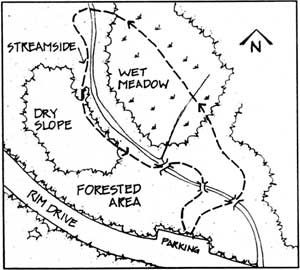

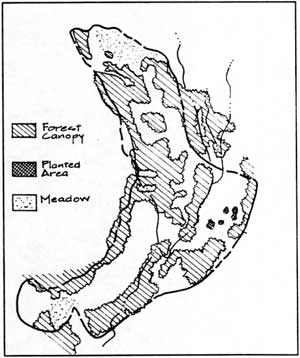

|

|

Natural features of the Castle Crest Wildflower Trail. No scale. |

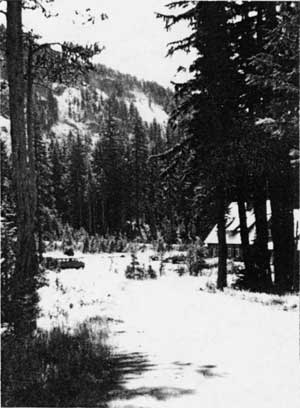

“In order that visitors unable, through lack of time or physical strength, to visit all parts of the park may see and enjoy as many varieties as possible of the exquisite wild flowers that abound in out-of-the-way places, wildflower gardens have been constructed in several of the national parks.”(1) Visitor accessibility was the incentive behind construction of the Castle Crest Wildflower Garden east of the Administrative plaza in 1929. Chief naturalist Ansel Hall (1923-1930), of the NPS Research and Education Branch, may have directed the layout of the .4 mile loop trail and organized the presentation of interpretive information. The trail contained at least 29 interpretive stops through an area of forest, swamp, wet-meadow, and grassy slope featuring native wildflower display and an occasional glimpse of wildlife through the spring and summer seasons. Boy Scouts constructed the trail and attached aluminum identification labels to plant materials adjacent to the trail.(2) At an approximate construction cost of $160.00, the unpaved trail featured five log bridges and four rustic benches.

|

Park naturalist at the footpath access to the Castle Crest Wildflower Garden from the Administrative plaza, c.1930. (CRLA Park files) |

Establishment of the Castle Crest Wildflower Garden in 1929 may have been part of an NPS interpretive program to provide accessible and educational nature trails. Other gardens developed at this time include a garden at the Ahwahnee Hotel in Yosemite Valley and an area adjacent to the Museum and Administration building at Giant Forest in Sequoia National Park. Both garden designs used transplanted materials from other areas in the parks to exhibit a “profuse” array of native flowers and to attract wildlife. In contrast, park records indicate that plant materials of the Castle Crest garden were not imported but are indigenous to the site. Trail construction and interpretive devices constitute the only design elements of the site.

Research to-date suggests that the historical significance of the Castle Crest Trail is a designed landscape associated with NPS interpretive programs of the mid-1920s to mid-1930s, and the work of naturalist and forester Ansel F. Hall. Hall’s NPS career (c.1920-1938) included terms as senior naturalist and chief forester, and chief of the Field Division. His vision for environmental education in national parks combined a deep feeling for youth and nature. Hall’s “plans” were ready for implementation when the New Deal public works programs were formed. He brought private funds and public involvement to the parks as he developed the first museum association at Yosemite and organized Eagle Scout trips in park areas. Although further research is required to properly assess the historic contexts and significance of the Castle Crest Wildflower garden, the site possesses many of the design features and qualities from the original design. Additional field investigation is required to assess the site boundaries and the extent of historic materials present at the site.

Suggested research topics include: Boy Scouts of America; history of interpretation in the National Park Service; and the history of accessible design, general and NPS.

PLANT LIST OF THE CASTLE CREST WILDFLOWER GARDEN

| Trees | |

| Abies lasiocarpa | subalpine fir |

| Abies magnifica shastensis | Shasta red fir |

| Pinus albicaulis | whitebark pine |

| Pinus contorta | lodgepole pine |

| Pinus monticola | western white pine |

| Tsuga mertensiana | mountain hemlock |

| Shrubs | |

| Arctostaphylos nevadensis | pinemat Manzanita |

| Dicentra formosa | Pacific bleeding heart |

| Eriogonum umbellatum | sulfer eriogonum |

| Gilia aggregata | skyrocket gilia |

| Haplopappus bloomeri | rabbitbrush goldenweed |

| Kalmia polifolia microphylla | alpine bog kalmia |

| Luzula glabrata | smooth woodrush |

| Pachistima myrisinites | myrtle pachistima |

| Penstemon rydbergii | Rydberg’s penstemon |

| Ribes erythrocarpum | Crater Lake currant |

| Salix eastwoodiae | eastwood willow |

| Sambucus racemosa v.microbotrys | Pacific red elder |

| Sorbus sitchensis v.cascadensis | Sitka mountain-ash |

| Spirea densiflora | subalpine spirea |

| Vaccinium caespitosum | dwarf blueberry |

| Ground Covers | |

| Aconitum columbianum | Columbia monkshood |

| Agoseris aurantiaca | mountain dandelion |

| Agrostis hiemalis | ticklegrass |

| Agrostis idahoensis | Idaho bentgrass |

| Anaphalis margaritacea | common pearl-everlasting |

| Anemone occidentalis | western windflower |

| Calamagrostis canadensis | bluejoint |

| Castilleja miniata | scarlet paintbrush |

| Crytogramma acrostichoides | parsley fern |

| Deschampsia autropurpurea | mountain hairgrass |

| Dodecatheon alpinum | Alpine shooting star |

| Epilobium angustifolium | fireweed |

| Epilobium brevistylum | barbey |

| Filix fragilis | brittle fern |

| Grimmia alpestris | gray-green moss |

| Habenaria stricta | green bog orchid |

| Hackelia micrantha | blue stickseed |

| Hygrohypnum bestii | moss |

| Hypericum Scouleri | Scouler’s St. John’s wort |

| Juncus Parryi | Parry’s rush |

| Letharia vulpina | staghorn lichen |

| Ligusticum ligulatus Grayi | Gray’s lovage (licorice root) |

| Lupinus latifolius | KIamath lupine |

| Mimulus Lewisii | Lewis monkeyflower |

| Phlox diffusa | spreading phlox |

| Pogonatum alpinum | haircap moss |

| Polygonum bisfortoides | American bistort |

| Pseudoleskea altrovirens | light-green moss |

| Ranunculus Gormanii | Gorman’s buttercup |

| Senecio triangularis | arrowleaf groundsel |

| Sitanion Hanseni | Hansen’s squirrel-tail |

| Tofieldia occidentalis | western tofieldia |

| Trifolium longipes | long-stocked clover |

| Viola Macloskeyi | small white violet |

| Viola purpurea v.venosa | mountain violet |

NOTES

1. Bryant, Harold C. and Wallace W. Atwood Jr., Research and Education in the National Parks. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1932, 18.

2. Telephone conversation with CRLA park historian Stephen Mark based on Oral History Interview with former Boy Scout Drew Chick, September 17, 1991.

REFERENCES

Bryant, Harold C. and Wallace W. Atwood, Jr. Research and Education in the National Parks. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1932.

Crater Lake National Park. “A Trail Guide to Castle Crest”, current pamphlet, n.d.

Crater Lake National Park Archives. Park Naturalist Reports, July 31 – August 23, 1929. Crater Lake Oregon.

Crater Lake National Park. “Castle Crest Nature Trail”, pamphlet, n.d.

Crater Lake National Park. “A Delightful Walk” Reflections. Summer 1982, volume 6.

Greene, Linda W. Historic Resource Study, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. Denver: Denver Service Center, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1984.

Hitchcock, C. Leo and Arthur Cronquist Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1973.

“Much Educational Work to be Given at Crater Lake”, Gold Hill News. c.1931.

Report of Director of National Park Service. 1929.

Sontag, William H., Ed. National Park Service: the First 75 Years. Philadelphia: Eastern National Park and Monument Association, 1990.

Warfield, Ronald G. Crater Lake: the Story Behind the Scenery. Las Vegas: KC Publications, 1985.

Yocom, Charles F. Shrubs of Crater Lake. San Francisco: Crater Lake Natural History Association, Pisani Printing Company, 1964.

REFERENCES TO CONSULT

Brockman, C. Frank. Evolution of National Park Service Interpretation. 1977.

Hall, Ansel F. A Guide to Sequoia and General Grant National Parks. Berkeley: National Parks Publishing house, 1930.

—–, Guide to Yosemite: A Handbook of the Trails and Roads of Yosemite Valley and the Adjacent Region. San Francisco: Sunset Publishing house, 1920.

—–, Yosemite Valley: An Intimate Guide. Berkeley: National Parks Publication house, c.1929.

Mackintosh, Barry. Interpretation in the National Park Service: A Historical Perspective. Washington D.C.: History Division, National Park Service, 1986.

Rath, Frederick L. A Bibliography on Historical Organization Practices. Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1975.

Tilden, Freeman. Interpreting our Heritage: Principles and Practices for Visitor Services in Parks, Museums, and Historic Places. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957.

***previous*** — ***next***

west view showing the snow tunnel and north parking lot

west view showing the snow tunnel and north parking lot