The Geology of Crater Lake National Park, OregonWith a reconnaissance of the Cascade Range southward to Mount Shasta by Howell Williams

The Climax: Culminating Explosions of Pumice and Scoria

The Glowing Avalanches: Pumice and Scoria Flows

“Fossil Fumaroles”

Kôzu observed that for more than 6 weeks after the great explosions of Komagatake, white columns of gas rose from the surface of the pumice flows, and some of them formed small ash cones, depositing sulphur, ammonium chloride, and iron chloride at their mouths. In the area covered by the pumice fall, on the other hand, even where the deposit was more than 3 meters thick, there were neither fumes nor sublimates. The surface of the pumice flows was colored in streaks of yellow and brown, like a tiger skin, whereas that of the pumice fall was uniformly grayish white. These differences imply that the flows were much richer in gas and much hotter than the pumice fall. Measurements taken at a depth of 40 cm. below the surface showed that, in general, the temperature fell from about 350° to about 125° C. during the first 50 days. Thereafter the rate of cooling was much slower; in the next 100 days the temperature fell only from 125° to about 60° C., and during the next 640 days it fell to about that of the atmosphere. These measurements were taken on the flows where there was no special concentration of gas. But where gases were streaming off most abundantly, the temperatures were higher. At such places, temperatures of 450° and 510° C. were recorded between 8 and 11 days after the eruption, and more than 2 years later the temperatures at a depth of 40 cm. were still 99° and 60° C., respectively. Since the Komagatake pumice flows were thin and small compared with those of Mount Mazama, it cannot be doubted that the Mazama flows remained at higher temperatures for much longer periods. Being compact and almost cemented with dust, they must have been well insulated, and probably they continued to give off hot gases for many years, after the manner of the “sand flow” in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.

The signs of fumarolic action within the flows are abundantly displayed near the rims of the canyons about Crater Lake. Beyond a distance of about 10 miles from the former summit of the volcano they disappear, for by the time the flows had moved that far they had lost much of their gas.

|

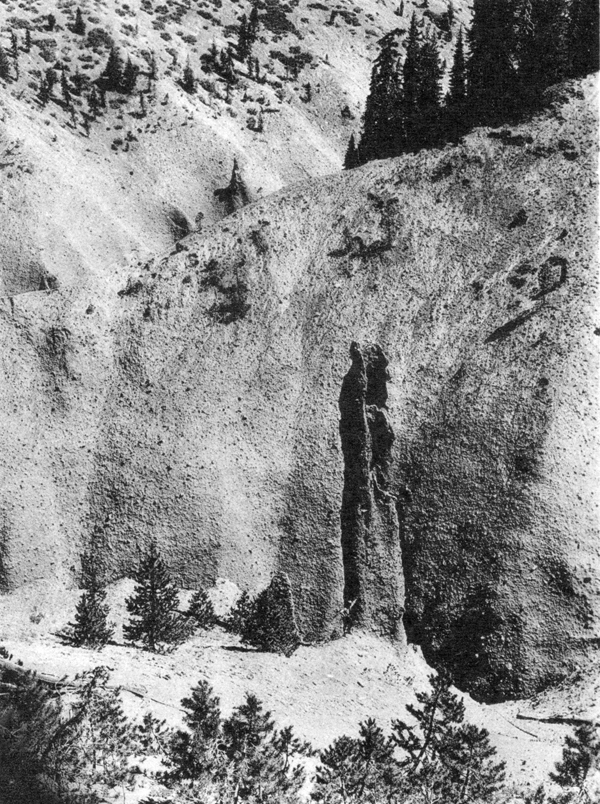

Plate 17. Fig. 2. “Fossil fumarole” in Castle Creek canyon. Note figure at the base for scale; note also the massive, unbedded, coarse nature of the deposits on the far wall of the canyon. (Photograph by National Park Service.) |

Visitors to Crater Lake entering along the valleys. of Annie and Sand creeks are familiar with the spectacular columns and spires that rise from the upper part of the canyon walls. These result partly from erosion of the pumice and scoria along vertical joints, and in this sense they are analogous in origin to the “earth pillars” commonly seen in “badlands.” But many occur where the pumice and scoria deposits are cut by vertical cracks the walls of which are cemented by iron oxides, kaolin, and opal. These are in fact “fossil fumaroles.” Brown, pink, and white streaks cut the gray scoria where the gases rose to the surface. Some of the spires are hollow inside and have irregular openings at the top. The largest of these tubular spires is 8 feet across and may be seen near Llao’s Hallway, in a tributary of Castle Creek. One of them is shown in plate 17, figure 2. All occur within the upper part of the scoria layer. On Sand Creek, as many as 150 “fossil fumaroles” may be counted in a distance of 1 1/2 miles along the canyon walls.