Research Natural Areas

As Aldo Leopold wrote, the first rule of intelligent tinkering is to save all the pieces. That thought is the rationale behind designation of research natural areas (RNAs) on selected federal lands in the United States. RNAs are administratively chosen (rather than legally created by Congress or a state legislature) to promote scientific research. They serve a threefold purpose: 1) as examples of significant ecosystems in a relatively undisturbed condition for comparison with those influenced by human activities; 2) as sites for scientific research as part of ecological and environmental studies; 3) as a reservoir of gene pools typical of endangered plants and animals.

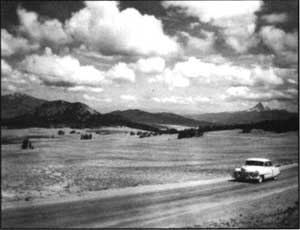

View of the Pumice Desert RNA. NPS photo, Crater Lake Museum and Archives Collections. |

RNAs in Oregon fill one or more “cells,” a construct used to inventory, classify, and evaluate natural areas. Cells are described in a natural heritage plan for the state and contain one or more of the following ecosystem elements: plant communities, special animal or plant species, aquatic types, other natural features. As part of a statewide conservation strategy, 93 RNAs have been designated in Oregon as of 1998. Four of those are located in Crater Lake National Park, where a nomination process initiated by the Nature Conservancy in 1986 eventually resulted in formal designation with concurrence from the National Park Service.

The largest RNA within the park consists of 3,055 acres and encompasses much of the Pumice Desert. All of this RNA lies west of the road connecting Rim Drive with the North Entrance, but is readily accessible to those visitors who stop at the pullout containing a wayside exhibit. Anyone who makes a short walk will find a largely barren area, one where infertile soil and severe temperature extremes restrict the number of plant and animal species residing in the Pumice Desert. This RNA nevertheless represents Oregon’s best example of two natural area cells, one being a lodgepole pine/Brewer’s sedge (Pinus contorta/Carex breweri)forest. The other is subalpine pumice and ash fields, created by Mount Mazama’s climactic eruption that covered a former glacial valley some 7,700 years ago.

Only 14 plant species have been recorded in the Pumice Desert, so botanists are justified in describing its flora as depauperate. Among the forbs, mountain buckwheat (Eriogonum marifolium) and pussypaws (Spraguea umbellata) dominate, though the comparatively rare Brewer’s sedge is abundant in small pockets. Despite the sparse vegetation, the Pumice Desert has attracted scientists interested in studying physiological adaptations by plants to harsh conditions. Another topic worth of further study is ecological succession in the area, one illustrated by the slow encroachment of lodgepole pine from the fringes of this seemingly desolate site.

Bitterbrush found in Desert Creek RNA. Drawings by Charles F. Yocum in Shrubs of Crater Lake, (Crater Lake Natural History Association, 1964), p. 29. |

If pumice and ash are defining characteristics of the Pumice Desert, they are also abundant in the park’s second largest RNA. It is an area of 1,869 acres, extending some two miles north and west of Sharp Peak. The closest vehicle access to the Desert Creek RNA is by way of road #2308 on the Winema National Forest, a route that approaches the so-called “golf course” from the north. Hikers can proceed up the usually dry watercourse of Desert Creek once they cross a fence whose purpose is to discourage cattle from grazing in the park.

The few people who venture to Desert Creek are attracted by the prospect of seeing a remnant plant community dominated by bitterbrush (Purshia tridentata), a shrub favored by the occasional pronghorn antelope (Antilocarpa americana). The presence of bitterbrush constitutes the main reason for this RNA because livestock grazing elsewhere has so decimated these shrubs. Old growth ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) can be seen in the upland part of this RNA, mainly because national park status for Crater Lake allowed these stands to escape the almost universal practice of selective logging east of the Cascades.

Llao Rock RNA not only lacks ponderosa pine, it contains hardly any shrubs or wood rush. Thick pumice deposits limit most of the understory to sedges in this area of 435 acres. Pumice does support tree islands or “atolls,” ones composed chiefly of mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana) and whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis). The latter can be found lining ridges or perched precariously near the caldera’s edge. Whitebark pine also represents the cell filled by this RNA within the larger statewide plan, even if this tree species is hardly unique to Llao Rock.

The RNA on Llao Rock was nominated primarily to protect known populations of two rare plants. Botanists once feared that the Crater Lake rock cress (Arabis suifrutescenvar. horizontalis) might be extinct, but the Nature Conservancy relocated these wildflowers while conducting its survey of potential RNAs in 1986. The other plant is known as the pumice grapefern (Botrychium pumicola) or Oregon moonwort, and can be found on level patches of course or “popcorn” pumice in two locations on Llao Rock. As a tiny green plant growing so close to the ground that it can be very difficult to see, the pumice grape fern is vulnerable to trampling. Hiking in this RNA is not prohibited, but please be careful where you step!

Access to the Llao Rock RNA is provided by Rim Drive, with several pullouts located just east of North Junction. Skiers will probably have an easier time of reaching the top than hikers who have to contend with uneven footing due to holes created by Mazama pocket gophers (Thomomys mazama). Wildflowers are relatively few, though colorful; similar habitats such as Cloud Cap or Grotto Cove offer easier access by vehicle.

Sundew in Sphagnum Bog. Photo by Willis Keithley, 1957.

Pumice grape fern. NPS photo, Crater Lake Museum and Archives Collections. |

The wildflowers present in the park’s fourth RNA, 180 acres in vicinity of Sphagnum Bog, contrast markedly from those found in areas dominated by dry pumice. Carnivorous sundews and bladderworts most readily come to mind when pondering a visit to the bog, but there is also a small population of the rare Mount Mazama collomia (Collomia mazama) within this RNA. More noticeable to the untrained eye are the pink and yellow monkeyflowers (Mimulus lewisii and M. primuloides) or the alpine shooting stars(Dodecatheon alpinum) that flower around Crater Springs. In all, approximately one quarter of the 150 plant species counted within the Sphagnum Bog RNA could be classed as wildflowers a number far exceeding the combined total of wildflower species for Pumice Desert, Desert Creek, and Llao Rock.

What makes Sphagnum Bog exceptional, however, is the diversity among its plant communities. In this respect it outpaces other bogs or mires in the Oregon Cascades. Sphagnum Bog not only contains eight plant communities, but the RNA also includes another three communities delineated by forest type. Aquatic communities are present at the springs, along streams, and in pooled water that is isolated but sometimes deep. The mix of communities in this RNA allows it to fill six cells identified by the Oregon’s natural heritage plan as needs in the west slope of the Cascade Range. These cells include flowing and pooled springs, Sitka sedge (Carex sitchensis) fen, Few flowered spikerush (Eleocharis pauciflora)/brown moss fen, Bog laurel (Kalmia microphylla)shrub swamp, Mountain alder (Alnus incana)/sedge community, and Bog blueberry(Vaccinium occidentale) shrub swamp.