A Tribute to Steve Robinson

Ranger Magazine

Spring, 2008

By BRIAN CAREY

Chiricahua and Fort Bowie

Webmaster’s Note: Steve was a former ranger naturalist at Crater Lake NP.

Most National Park Service seasonals do not arrive at the job site by sailing in from the sea, but that was Steve Robinson’s introduction to Flamingo at the southern terminus of Everglades National Park in December 1979. It was an inauspicious beginning since he was marooned in port after his sailing companion took the motor and jumped ship, advising Steve to find work.

|

|

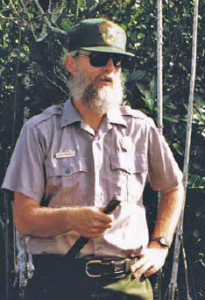

Steve Robinson |

A visitor to Flamingo in those years might remember the faded employment available sign that beckoned to wanderers low on cash and prospects. So Steve began his career in Flamingo as a houseman for the concession lodge, mostly because he played guitar. The concession manager also played a four-string tenor guitar and had a vision of the Buttonwood Lounge as a mecca for music and a happening nightlife. Steve, however, could not wait to become a naturalist and strum health into the Everglades. He had his opportunity soon after and began what was to become 25 continuous seasons of service as a park interpreter in one of the nation’s premier biological parks.

As a fourth generation Floridian, Steve was uniquely equipped to know the beauty of the state and the fragile nature of its ecosystems. Childhood photos posted on his memorial website show stringers of bass and bluegill and a west Florida background of oaks, palms and citrus that would all soon yield to the pressures of population growth. Steve was an environmentalist long before it was in vogue. He first showed concern at age 5 when his mom remembers him asking what she was doing about pollution. His passion for sports also manifested itself early, playing on a league-leading, fast-pitch softball team. Steve played guitar in a band, “The Tribesmen,” in Riverview, Florida, and at one time aspired to rock-and-roll fame. Among all of the distractions of youth in East Bay High School in the 1960s, Steve was conscious of the environmental issues of the day. He talked in earnest about Mother Nature to anyone who would listen. Steve canoed the Alafaya River, hunting snook and seining for sharks’ teeth. He contemplated living a life alone in nature. He bought a 24-foot Venture sailboat and set off to rediscover the lost wilderness of his youth, but he was 26 before he first visited the Everglades. A simple twist of fate landed him in Flamingo.

Steve was a provocative interpreter whose passion sometimes made others uncomfortable. In fact, that was one of his mottos for interacting with the world: comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. His was a passion and directness that was well respected by new and returning Everglades visitors alike. Unlike many interpretive staff, Steve loved working at the information desk and always drew a crowd with the obvious depth of his knowledge of the resource and the value of his tips for visiting the park. Returning visitors sought him out for updates on the state of affairs at the park, many times asking, “Where is the guy with the beard and the ponytail?” He was commanding. He always drew a crowd. It was easy to get swept up in his idealism, his unwavering vision of a beautiful, natural world.

The musical talents that he and his wife, Amelia Bruno, shared were also a source of inspiration at campfire programs, at interpretive training, and during the Everglades 50th anniversary celebration and innumerable park “coffeehouses.”

Crater Lake visitors were treated to Steve’s same eloquence about the natural and spiritual power of the park’s resources during his seasons as an interpreter and a fire lookout ranger. His dogged determination to improve the safety program for the boat tours of Crater Lake will continue to reap benefits for the park.

Steve’s real legacy will undoubtedly be the many young interpreters he tutored, mentored, inspired and befriended. The pages of his memorial site are scattered with comments like this: “I was an impressionable young seasonal ranger at Flamingo in the late ’80s, and the impression you left on me was one of a person who wasn’t afraid of fighting.” Or “Steve and Amelia . . . you’re the soul of Flamingo. You all have made such a positive difference.” And “Because of your love and your Marjorie-like stubborn determination, I refuse to ever give visitors the impression that the Everglades or the planet is beyond hope.”

Steve died as peacefully as he lived. At 10:25 in the morning on Oc. 1, 2007, Steve looked at Amelia and son Darby and quietly stopped breathing. He had been a partner and soulmate; a patient, loving dad whose heart burst with pride when Darby was born; and an honest, compassionate, fast and true friend. His gifts as a rock-folk guitarist and music teacher brought out the best in everyone. He was an Everglades expert who felt that his mentor, Marjorie Stoneman Douglas, had passed the torch to him when she heard him speak at the Anhinga Trail and approved of his message.

Steve’s strength came from times spent in nature. His 24-hour solo sails to Sandy Key were vital to his psyche. He found his life’s worth in being an NPS naturalist.

For the past two years he had remained in Oregon, avoiding hurricanes in Florida and helping his son get established in college. But he was going back this year — a year that needed his voice more than ever, a year when the Everglades is being removed as a World Heritage Site.

For many who remember Florida Bay sunsets, an image will always linger: the silhouette of Steve, standing up in his canoe as it slides across the water under sail, a ghost of the Calusa Indians that also plied these estuarine waters. It’s a fitting image to carry into the future for the countless visitors and NPSers who were helped, inspired and moved by this man and his genuine love for nature.

He wanted to change the world. He succeeded.

Brian Carey is a 27-year veteran of the NPS, currently serving as superintendent of Chiricahua National Monument and Fort Bowie National Historic Site. This article was composed with generous contributions from Amelia Bruno, Steve’s partner and best friend. She is the fee program manager at Crater Lake.

***previous title*** — ***next title***