***previous*** — ***next***

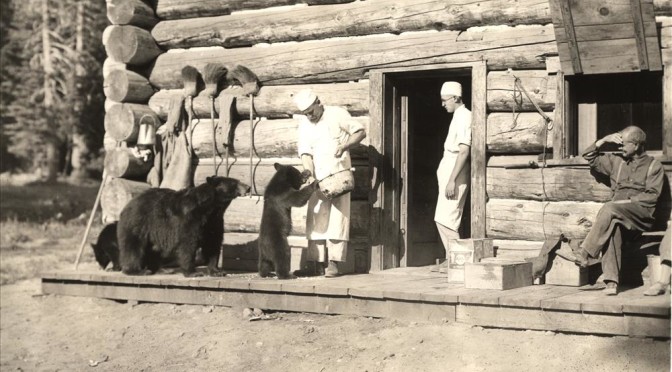

above, Will Steel sitting far right

William Gladstone Steel –

The Father of Crater Lake National Park

A chronology complied by Stephen R. Mark

Historian, Crater Lake National Park

1854 Born on September 7 in Stafford, Ohio. His father was a Scottish immigrant who came to Virginia in 1817 at age 8. His mother was a Virginia native, the former Elizabeth Lowry.

1868 Steel family left Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for southeastern Kansas on March 25. They settled on a farm near Oswego in Labette County.

1870 Read about Crater Lake for the first time, supposedly in a newspaper containing his lunch. (It was a copy of the Oregonian sent out by his brother who was living in Portland, Oregon at the time.)

1872 Family left Kansas for Portland, Oregon, where they joined two of Will’s brothers who had become successful financiers.

1873 Will completed high school in Portland and began a three-year apprenticeship as a pattern maker for Smith Brothers Iron Works. Started collecting newspaper clippings to place in scrapbooks.

1875 Is said to have acquired an interest in mountaineering.

1879 Father William Steel died January 5. Later that year Will became president of Portland’s Philomathean League, a society for oratory and debate. In October he established the Albany, Oregon Herald in an attempt to carry Linn County for the Republican Party. The paper was sold the following summer.

1881 With his brother David, Will initiated publication of a promotional journal called The Resources of Oregon and Washington in November. Their main business associate was Chandler B. Watson, who had visited Crater Lake 1873.

1885 Steel arrived at Crater Lake for the first time on August 15. Two days later he christened Wizard Island. On his return to Portland, Steel consulted with Judge John B. Waldo in Salem about a proposal to establish Crater Lake as a national park. Will’s professional status at this time was as superintendent of postal carriers in Portland, owing to his brother George being postmaster.

1886 At Steel’s urging, two national park bills were introduced in Congress during January. On February 1 President Cleveland reserved 10 townships around the lake fro settlement. Will directed the transport of equipment for a U.S. Geological Survey expedition to Crater Lake in July.

1887 On July 4 was the first person to successfully illuminate Mt. Hood at night. Organized the Oregon Alpine Club in September.

1888 Met John Muir for the first in August at Mt. Rainier. During that month Steel planted the first fish in Crater Lake and made his only known journey to the Oregon Caves.

1889 Attempted to find investors for a railroad to run from Drain to the mouth of the Umpqua River. Assisted in the reorganization of the Oregon Alpine Club.

1890 Published his only book, The Mountains of Oregon, through his brother David. That summer Steel had the Oregon Alpine Club cosponsor the O’Neil expedition of the Olympic Mountains.

1891 Formed a real estate partnership called Wilbur & Steel in Portland. For the next two decades Steel assisted with the development of North Portland, especially the area near what is presently University Park and Portsmouth.

1892 OAC declared bankruptcy after Steel used $1000 of his own money for its operation.

1893 A four million acre Cascade Forest Reserve was established by executive order. The predecessor to several national forests and Crater Lake National Park, Steel and Waldo played the largest role in lobbying for its creation.

1894 Organized the Mazamas on the summit of Mount Hood on July 19. Some 193 people made the ascent, many from Steel’s cabin near Government Camp.

1895 Traveled to Washington, D.C. to foil the first Congressional attempt at rescinding the Cascade Forest Reserve.

1896 Led a Mazama trip to Crater Lake in August. Steel also facilitated the investigations of several government scientists in conjunction with the gathering. Later in the month he brought the National Forestry Commission to the lake. Founded the Oregon Forestry Association as result of his interest in Pacific Northwest forests.

1897 Failed to secure a patronage appointment as superintendent of the Cascade Forest Reserve. During the summer and fall worked as a forest reserve surveyor for the U.S. Geological Survey in the vicinity of Stehekin, Washington.

1900 Married Lydia Hatch in Portland on February 16, at age 46.

1901 Steel’s fish planting of 13 years before was declared a success when trout were discovered in Crater Lake.

1902 After 17 years of painstaking effort, Steel was triumphant when Crater Lake National Park was established on May 22.

1903 Brought 27 people to Crater Lake from Medford on August 5. This was his first attempt to provide visitor services at the lake.

1906 Initiated publication of a pamphlet series called Steel Points. Resigned from Mazamas on August 30.

1907 Established the Crater Lake Company with E.D. Whitney in Portland on June 6. As the park’s first concessioner, he provided transportation for tourists, a tent camp at Annie Springs and boat tours on the lake.

1909 Opened Camp Crater at the rim on July 20. After choosing the site where the Mazamas gathered in 1896, Steel supplied the funds to begin construction of the Crater Lake Lodge.

1912 Secured federal funds for the construction of a road around Crater Lake. Sold his financial interest in the Crater Lake concession to his Portland real estate partner, A.L. Parkhurst.

1913 Appointed as Crater Lake National Park’s second superintendent.

1914 Endorsed government ownership of the park’s concessions as a way of helping the faltering Parkhurst complete his development at the rim.

1915 Was on hand when the partly completed Crater Lake Lodge opened on July 3. After a visit by William Jennings Bryan, Steel recommended that an elevator be constructed from near the lodge to the lakeshore.

1916 Resigned as superintendent on November 20 in order to accept the position of park magistrate. The job as magistrate was created after the State of Oregon ceded jurisdiction over Crater Lake to the Federal Government a year earlier.

1920 Took up residence in Eugene.

1921 Rejoined the Mazamas.

1924 Published a pamphlet titled “The Crater Lake Scandal” on January 1. It was written to protest the treatment of Parkhurst, who had been forced to give up the Crater Lake concession in 1920.

1925 His speech before a Eugene service club on Lincoln’s birthday was self-published, as was a volume of Steel Points Junior called “Crater Lake Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow”.

1927 Published his last pamphlet, a volume of Steel Points Junior.

1929 Relocated to Medford. Its newspaper reported Steel’s intent to assist with the growth of Oregon’s state park system once the parks had been incorporated into the State Highway Division.

1932 Initiated a campaign to build a road inside the caldera from Rim Village on May 22. Made his last visit to Crater Lake that summer, after which he suffered a long illness. Lydia Steel died in Medford on November 9.

1934 Died November 21. Buried in Medford’s Siskiyou Memorial Park wearing his NPS uniform.

Steve Mark writes: Born in Ohio, William Gladstone Steel finished high school in Portland, Oregon. He became a postal carrier after short stints as a newspaperman, railroad promoter, and publisher. His first visit to Crater Lake came on a short vacation from the Portland post office in 1885. Steel and a friend went to southern Oregon to meet up with geologist Joseph LeConte who was studying the volcanic features of the Pacific Coast. After seeing the lake for the first time, Steel wrote:

Not a foot of the land about the lake had been touched or claimed. An overmastering conviction came to me that this wonderful spot must be saved, wild and beautiful, just as it was, for all future generations, and that it was up to me to do something. I then and there had the impression that in some way, I didn’t know how, the lake ought to become a National Park. I was so burdened with the idea that I was distressed. [For] Many hours in Captain Dutton’s tent [Dutton was head of a small military party assigned to accompany LeConte], we talked of plans to save the lake from private exploitation. We discussed its wonders, mystery and inspiring beauty, its forests and strange lava structure. The captain agreed with the idea that something ought to be done–and done at once if the lake was to be saved, and that it should be made a National Park.(9)

Upon returning to Portland, Steel began circulating a petition that eventually found its way to the state legislature. It was favorably received and a resolution recommending a public park around Crater Lake was forwarded to the Secretary of the Interior Lucius Q.C. Lamar. As a result, ten townships were withdrawn from entry by executive order of President Grover Cleveland on February 1, 1886.(10)

- Quoted in Harlan D. Unrau, Administrative History Crater Lake National Park, Oregon, USDI-National Park Service, (Denver: NPS, 1988), 27-28. Steel has a different account in “Crater Lake and How to See It”, The West Shore 12:3 (March 1886), 104-106; also “Crater Lake Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow,” Steel Points Junior 1:2 (August 1925), n.p.

- Special Session, Oregon Legislature, “S.J.M. No. 5”, adopted November 18, 1885, Steel Letters, Box 1, Item 211, Museum Collection, Crater Lake National Park. Executive Order, February 1, 1886, Record Group 49 [General Land Office], Division R, Box 125, Rogue River file, National Archives, and “The President’s Order”, Steel Points, 1:2 (January 1907), 73.

***previous*** — ***next***

***menu***