National park status for Oregon’s Crater Lake took time, patience and a man named Steel

Saturday, May 21, 2011, By John Terry, Special to The Oregonian

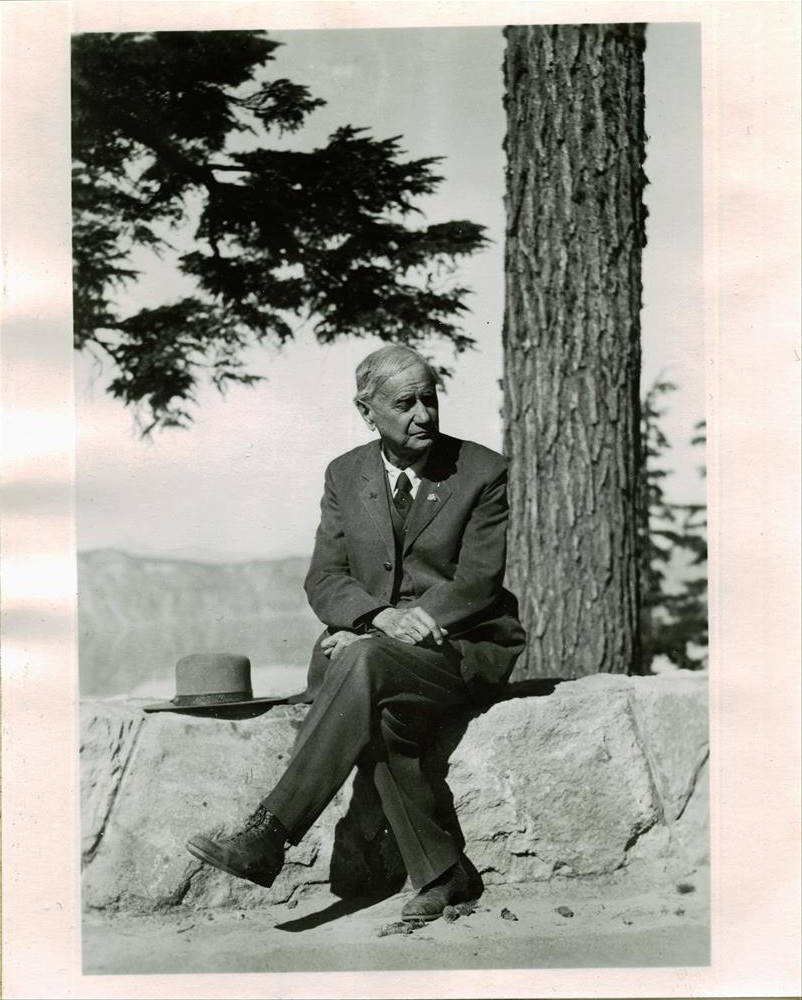

William Gladstone Steel campaigned long and hard to get Crater Lake designated as a national park. Happy birthday, Crater Lake National Park, which turns 109 Sunday.

On May 22, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the bill creating the park. His signature capped a 17-year campaign to ensure Oregon’s natural wonder would remain largely unsullied.

And at the forefront of the Crater Lake crusade was an ardent Eastern transplant, William Gladstone Steel.

Crater Lake has been with us since the massive eruption and collapse of 11,000-foot (or more) Mount Mazama 7,500 years ago. For some Native Americans in the region, it was Gilwas or “Sacred Place.” Early white visitors dubbed it Blue Lake and Lake Majesty.

Itinerant prospectors first reported coming on it in 1853. One group reported it to the Jacksonville Sentinel newspaper in 1862.

Two members of the First Oregon Volunteer Infantry also “found” it while hunting in 1865. They reported it to their captain, who was “apparently unaware of the site and its previous two ‘discoveries,'” wrote historian Rick Harmon in “Crater Lake National Park, A History” (Oregon State University Press, 2002).

Sentinel editor James M. Sutton and others explored in 1869 and christened it Crater Lake. Photographer Peter Britt snapped some pictures in 1874, revealing it to the world.

“… By the mid-1870s, Crater Lake had become a well-known local tourist attraction admired both for its beauty and its commercial-recreational potential,” Harmon wrote.

Steel first visited on Aug. 15, 1885, fulfilling an ambition nurtured since he came to Portland from Kansas at age 18 in 1872. He claimed he first read of the lake in a Kansas newspaper wherein was wrapped his lunch. It was from a copy of the Oregonian that had been sent out to the family in Kansas, by his brother who was living in Portland, Oregon at the time.

“This article took a great hold upon me,” he said. “So great that I determined then and there to go to Oregon to descend to the water to climb (Wizard Island) and to take my lunch there.”

Steel worked at a variety of Oregon jobs, including newspapering. Around 1875, he took to mountaineering like the proverbial mountain goat, his biographers say. Ten years later, his first look at the lake’s jaw-dropping beauty engendered his passion.

Steel’s 1885 petition to President Grover Cleveland urged establishment of the park. It was chock-a-block with prominent, and politically ranking, Oregon signatories.

“He was very focused,” park historian Stephen Mark said. “He had a great sense of what was right, and once committed to that course would never give up.”

In 1886, Steel sent nearly 1,000 letters “to nearly all the large daily newspapers in the United States” soliciting support for the park, Harmon wrote. A bill to form the national park failed in Congress, but prompted Cleveland to ban settlement in 10 townships around the lake.

William Gladstone Steel enlisted prominent naturalists in his cause. He constantly pestered congressmen and senators.

Other park bills were introduced. Congress dithered and balked. Cleveland in 1895 created the vast Cascade Forest Reserve. Steel saw that as opening the door to the national park. Congress saw otherwise and tried to rescind it. Steel went to Washington to fight for it and, along with others, won.

Once the 1902 park bill passed, Steel continued as the lake’s No. 1 advocate. He was miffed that he wasn’t appointed its first superintendent. Nevertheless, he pushed it as a tourist attraction. In 1913, he got the job but resigned three years later amid controversy over his ambitious development plans.

He was appointed park commissioner at a salary of $1,500 a year. “This quasi-judicial position required the incumbent to live in the park and officiate proceedings on violations of park rules and regulations,” Harmon wrote.

Steel continued to preach the Crater Lake gospel far and wide. His last visit was in November 1932. He died Nov. 21, 1934, and was buried in Medford, dressed in his National Park Service uniform.

The Oregonian praised him as the “Father of Crater Lake Park.” Numerous other outdoor achievements were his as well. In 1894, he founded the Mazamas mountaineering club.

“He was always starting some sort of club,” Mark said, “but most of them didn’t last very long.”

Steel professed little literary ability, but Crater Lake inspired him.

“To the west, the sun was slowly sinking to rest, when a glowing light spread itself over the dark clouds, which became brighter and still brighter,” he wrote of one visit. “… Here and there were tints of crimson, the delicacy of which no artist could approach.”

— John Terry

***previous*** — ***next***

***menu***